Mon 14 Dec 2020

Click here to read the story of Ihumātao, as told by Pania Newton.

Why this experience impacted me:

It was always my wawata (aspiration) to hear the story of Ihumātao from the people themselves. When I heard it was Pania who would take us through their kōrero, I couldn’t help but be excited. I was captivated by the beauty of the place and by Pānia from the very moment we were called onto Makaurau marae. To be able to be on the landscape, to see it, smell it, feel it, and to hear the story being told by Pania, had elevated my awareness and aroha for Pania, her whenua, whānau, and tūpuna and the the struggles that they’ve had to endure. She opened all of our eyes to the continued injustices that our people, Māori, are still faced with in Aotearoa New Zealand. More importantly, she gave me hope. Hope that there will be a better future for our nation, Māori mai, tauiwi mai.

She appeals to our human emotions through stories of resilience. Pania and her whānau use these pūrākau and histories to draw strength and resilience for herself and her people. These stories keep them going. They have kept her resolute and unwavering in her stand against the confiscation of her papakāinga (communal Māori land) at Ihumātao.

She told us about the quarrying of her maunga (mountain). Nō hea kē au ka whakaae ki tēnā! I would never stand for that! I could not fathom my maunga – Maungataniwha, Mōtatau and Whakarārā – being butchered and dug away into non-existence. I could feel the despair and the hopelessness Pania spoke of. The injustices and suffering Pania’s people have endured is a common story among our people.

I place Pania and her whānau among some of the greats of Te Ao Māori; among the likes of Te Whiti-o-Rongomai and Tohu Kākahu of Te Āti Awa who led the non-violent resistance at Parihaka in 1880s; of Dame Whina Cooper of Te Rārawa who headed the Māori land march in 1975; and Ngāti Whātua who occupied Takaparawhā in 1977-78; and the Whanganui people who occupied Pākaitore in 1995. Just as Dame Whina Cooper said “not one more acre,” Pānia plants her waewae (feet) firmly in her whenua (land) and says “enough is enough!” (personal communication, 14 Dec 2020).

What made this experience so special was that we were able to go and watch the sunset on the ‘reclamation site’ of Ōtuataua. As we watched the sunset, I felt hopeful. Hopeful that their suffering and injustices will set with the sun, and that a positive outcome awaits them on its rising. And indeed happy news arrived at Ako Mātātupu on Wednesday 17 December when the government announced the good news. They would get their whenua back.

What I learned and will take into my classroom:

- Use stories of my papakāinga to draw strength for students and whānau

- Be a weaver of stories and hearts: Pania demonstrated mastery and skill at karanga, pao, storytelling. She was able to appeal to our human emotions to enable us to relate to their mamae (hurt), to their suffering. She was skilled also at interweaving past, present and future. Kāhore i kō atu, i kō mai – I haven’t seen anything like it.

- Know your stuff, but also be open to what is happening around you: she demonstrated awareness and knowledge of Māori and Pasifika histories and how they interconnected. I learned of the importance of Ihumātao as being the oldest papakāinga (communal Maori land) in Tāmaki Makaurau.

- Incorporate our histories into your lessons – make it a unit of work: why is it important to learn about our histories? Through pūrākau (stories) and history she taught us the significance of Ihumātao to the Auckland and Aotearoa New Zealand story. I hope to bring my students to Makaurau marae as part of one of their experiences outside the classroom.

- Understand why Maori are at the bottom of the heap: the impacts of land confiscation and colonisation in Aotearoa has been felt for generations by our people. It has generated feelings of hopelessness among our people. It is what Jessica O’Rogers calls ‘historical trauma.’ It is this historic trauma that has had a catastrophic effect on our people. The disconnection from whenua (lands), from culture, from language and identity, and lack of place and belonging have caused major disruptions over the years. This is a major contributing factor to why our people are at the bottom of the heap here in Aotearoa.

- Fight for the mana motuhake and tino rangatiratanga of your students: “enough is enough” said Pania (personal communication, 14 Dec 2020). Despite the adversity, challenges and anxieties Pania and her whānau had to endure they knew it was too important to give up. They stayed and did the hard yards for four years reclaiming their whenua. Pania and her whānau were driven by the ōhākī (parting wish) of her whānau, and of her tūpuna (ancestors) to uphold the mana motuhake (independence) and tino rangatiratanga (self-determination) of her people.

- Promote collective-efficacy: research has shown that creating a whānau environment in the classroom promotes improved outcomes (Milne, 2006; Bishop, 2019). Pania would always talk about the story within a collective context. She did not see anything she has been doing as an individual effort. She used words like, “whānau,” “ours,” “we,” “my tūpuna,” “tamariki.” I never heard her say ‘I’. Novelist Sia Figiel (1996) offers a salient literary example of the fa’a Samoa ‘I’ in her debut novel Where We Once Belonged:

“I” does not exist. I am not…“I” is always “we,” is part of the ‘aiga (extended family)…a part of the nu’u (village), a part of Samoa”

Sigiel, 1996, p.135

- Make your students accountable to something bigger than themselves – their class, their school, their community: Pania fosters a sense of community and you can hear it, you can see it. Research has shown that fostering a connection to community, to something bigger than ourselves, can be what Delpit (2006) posits, “can propel our children to be the best” (p.230). You need only to look at Pania and what her and her whānau at Ihumātao have accomplished.

- Whakapapa does not need to validated: we came into this kaupapa knowing that the government’s resolution for the dispute at Ihumātao was due to be announced that very week. It was business as usual for Pania. They did not need the Crown’s validation to legitimise their claim and whakapapa to their whenua. Pania said, “we are winning everyday that we are on our whenua” (personal communication, 14 Dec 2020).

- Mā whero, mā pango e oti ai te mahi – with the cooperation and combined efforts of student, whānau, and community, they can achieve their goals: happy news arrived at Ako Mātātupu on Wednesday 17 December when the government announced that they will pay Fletcher out and build houses on the whenua in a manner agreed to by the Kīngitanga and the Auckland Council. Having a positive outcome was much needed especially during a year that saw covid-19 bring the world to its knees (click here to watch the announcement). The Māori whakatauki, “mā pango, mā whero ka oti te mahi” usually refers to different peoples or groups cooperating and combining efforts to achieve their goals.

How can I can incorporate Pania’s stories into my classroom?

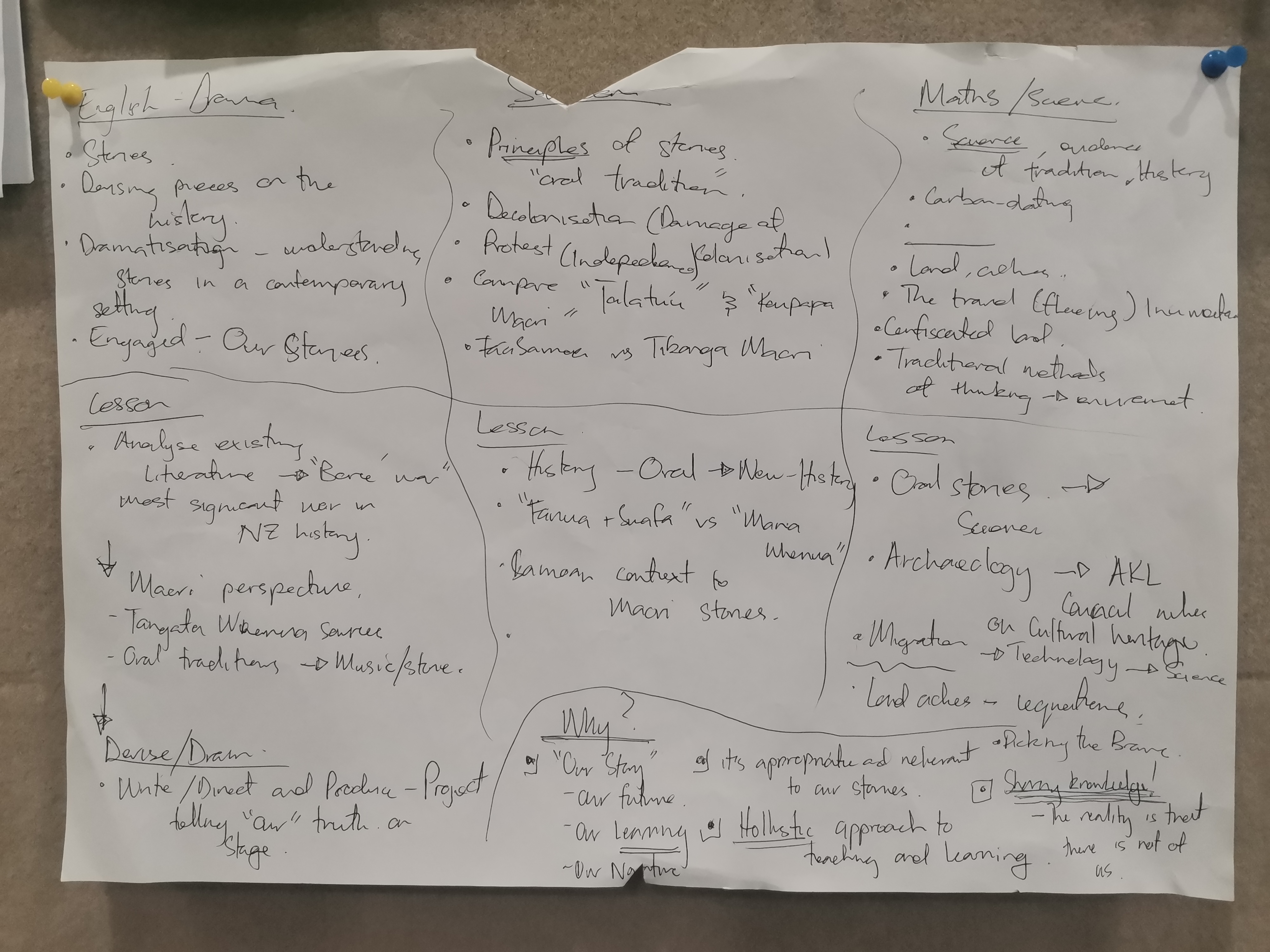

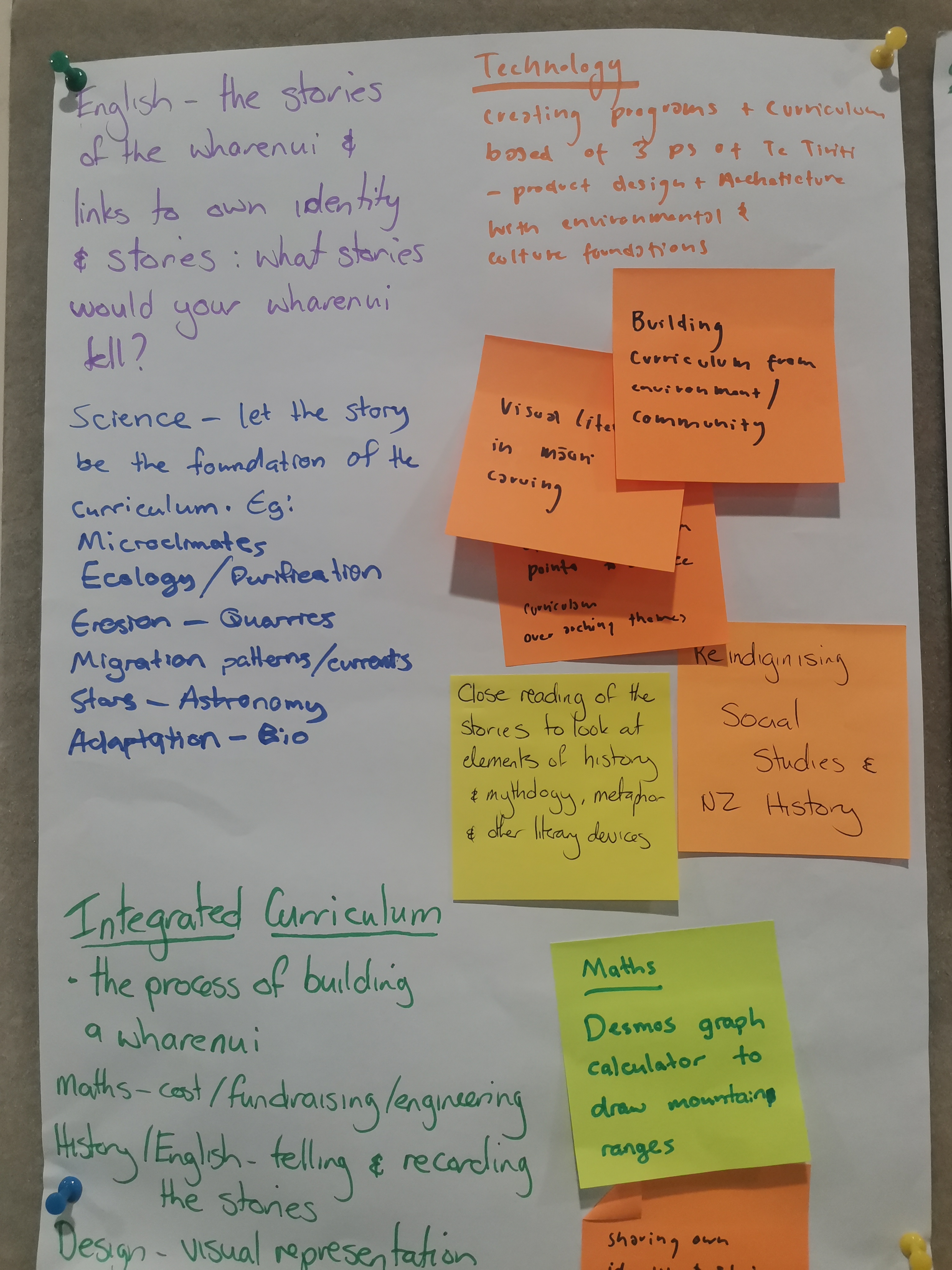

Cross-curricular activities

- Science:

- Astronomy and navigation.

- Explore volcanoes around Auckland analysing their biology and the changes they have undergone since Pākeha arrival.

- Environment and community projects (i.e., agriculture).

- Archaeology of heritage site – carbon dating.

- Explore aquifers and pollution of local rivers.

- the costs of capitalism – of having flushing toilets or tar-sealed roads.

- Micro-climates to grow kai or other native plants in Auckland region (e.g., Rangitoto).

- Maths:

- Discover how Hape beat the Tainui waka;

- Navigation.

- Portaging the waka Tainui across from Ōtāhuhu;

- how many people were needed, etc.

- Navigation and design of a waka hourua;

- how it floats.

- what prevents it from capsizing.

- difference between waka taua (war canoe) and waka hourua.

- astronomy and stars.

- observing current patters and migratory mammals.

- Art and Drama:

- Create graphic books about the legends.

- Re-storying methods – like Peter O’Connor and Bishop (2019) – tell the story up to when Hape is left behind and have the class co-construct the story.

- Dramatisation of technological decline: “There is no more oil, water levels are too low, no electricity, therefore no more technology, what would you? How would you help to heal the environment? How would you survive?”

- Play about the legend.

- Reimaging Māori and Pasifika history through art: what would they have looked like? What would Hawaiki looked like?

- English:

- Write letters to the principal about something that needs rectifying in the school.

- Creative writing ideas;

- what would the pou of your whare or fale say to you if they could still speak.

- re-imaging Māori and Pasifika history: what would they have looked like? What would Hawaiki have looked like?

- how would you feel if your Island sunk, or if you mountain was quarried away?

- Social Studies:

- Compare Pania and media version of the story of Ihumātao.

- History:

- Lapita pottery history of Pacific migration.

- Māori and Pasifika as navigator of foreign spaces, of the unknown: if our ancestors can navigate foreign spaces, so can our Māori and Pasifika students navigate the Pākeha space (school).

- history of (place)names: local history, Pacific history, have the lands been lost?

- Māori:

- Education outside of school: travel to Ihumātao to hear Pania tell her story; or,

- Pania to come to class to tell her kōrero.

- carved stories.

- learn the processes of building a waka (canoe) and a whare whakairo (carved meeting house)

- compose waiata, haka, mōteatea: what would we want our descendants to know about our life?

- reconnecting with whenua projects.

Why does it matter?

- It is honouring Te Tiriti o Waitangi as treaty partners

- We are valuing other worldviews

- Broadening cultural diversity of the classroom

- Builds off of prior knowledge of the students

- The stories stay alive

- Evidence of their mana whenua status at Ihumātao

Standards and Competencies

I have measured Pānia’s competency in demonstrating aspects of the Standards for the Profession and Tātaiako as a Leader.

| Standard / Competency | Leaders |

| Standard 1: Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership Demonstrate commitment to tangata whenuatanga and Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership in Aotearoa New Zealand. | – Understand and recognise the unique status of tangata whenua in Aotearoa New Zealand. – Understand and acknowledge the histories, heritages, languages and cultures of partners to Te Tiriti o Waitangi. – Practise and develop the use of te reo and tikanga Māori. |

| Standard 4: Learning-focused culture Develop a culture that is focused on learning, and is characterised by respect, inclusion, empathy, collaboration and safety. | – Develop learning-focused relationships with learners, enabling them to be active participants in the process of learning, sharing ownership and responsibility for learning. – Foster trust, respect, and cooperation with and among learners so that they experience an environment in which it is safe to take risks. – Demonstrate high expectations for the learning outcomes of all learners, including for those learners with disabilities or learning support needs. – Create an environment where learners can be confident in their identities, languages, cultures and abilities. – Develop an environment where the diversity and uniqueness of all learners are accepted and valued. |

| Tātaiako: Whanaungatanga Actively engages in respectful working relationships with Māori learners, parents and whānau, hapū, iwi and the Māori community. | – Is visible, welcoming and accessible to Māori parents, whānau, hapū, iwi and the Māori community. – Actively builds and maintains respectful working relationships with Māori learners, their parents, whānau, hapū, iwi and communities that enable Māori to participate in important decisions about their children’s learning. – Demonstrates an appreciation of how whānau and iwi operate. – Ensures that the school/ ECE service, teachers and whānau work together to maximise Māori learner success. |

| Tātaiako: Manaakitanga Demonstrates integrity, sincerity and respect towards Māori beliefs, language and culture. | – Actively acknowledges and follows appropriate protocols when engaging with Māori parents, whānau, hapū, iwi and communities. – Communications with Māori learners are demonstrably underpinned by cross-cultural values of integrity and sincerity. – Understands local tikanga and Māori culture sufficiently to be able to respond appropriately to Māori learners, their parents, whānau, hap and Māori community about what happens at the school/ECE service. – Leads and supports staff to provide a respectful and caring environment to enable Māori achievement. – Actively acknowledges and acts upon the implications of the Treaty of Waitangi for themselves as a leader and their school/ECE service. |

| Tātaiako: Tangata Whenuatanga: Arms Māori learners as Māori – provides contexts for learning where the identity, language and culture (cultural locatedness) of Māori learners and their whānau is armed. | – Consciously provides resources and sets expectations that staff will engage with and learn about the local tikanga, environment and community, and their inter-related history. – Understands and can explain the effect of the local history on local iwi, whānau, hapū, the Māori community, Māori learners, the environment and the school/ECE service. – Actively acknowledges Māori parents, hapū, iwi and the Māori community as key stakeholders in the school/ECE service. – Ensures that teachers know how to acknowledge and utilise the cultural capital that Māori learners bring to the classroom in order to maximise learner success. |

| Tātaiako: Wānanga Participates with learners and communities in robust dialogue for the benefit of Māori learners’ achievement. | – Actively encourages, supports and, where appropriate, challenges Māori parents, whānau, hapū, iwi and the community to determine how they wish to engage about important matters at the school/ECE service. – Actively and routinely supports and leads stato engage eectively and appropriately with Māori parents, whānau, hapū, iwi and the Māori community. – Actively seeks out, values and responds to the views of Māori parents, whānau, hapū and the Māori community. – Engages the expertise of parents, whānau, hapū, iwi and Māori communities in the school/ECE service for the benefit of. |

| Tataiako: Ako Takes responsibility for their own learning and that of Māori learners | – Consciously plans and uses pedagogy that engages Māori learners and caters for their needs. – Plans and implements programmes of learning that accelerate the progress of each Māori learner identified as achieving below or well below expected achievement levels. – Actively engages Māori learners and whānau in the learning (partnership) through regular, purposeful feedback and constructive feed-forward. – Validates the prior knowledge that Māori learners bring to their learning. – Maintains high expectations of Māori learners succeeding as Māori. – Takes responsibility for their own development about Māori learner achievement. – Ensures congruency between learning at home and at school. |

| Tapasā Turu 1: Identities, languages and cultures Demonstrate awareness of the diverse and ethnic-specific identities, languages and cultures of Pacific learners. | 1.1 Understands his or her own identity and culture, and how this influences the way they think and behave. 1.2 Understands the importance of retention and transmission of Pacific identities, languages and cultural values. 1.3 Is aware of the diverse ethnic-specific differences between Pacific groups and commits to being responsive to this diversity. 1.4 Understands that Pacific world-views and ways of thinking are underpinned by their identities, languages and culture. |

| Tapasā Turu 2: Collaborative and respectful relationships and professional behaviour Establishes and maintains collaborative and respectful relationships and professional behaviours that enhance learning and wellbeing for Pacific learners. | 2.2 Understands that there are different ways to engage and collaborate successfully with Pacific learners, parents, families and communities. 2.3 Is aware of the importance of respect, collaboration and reciprocity in building strong relationships with Pacific learners, their parents, families and communities. |

| Tapasā Turu 3: Effective Pacific pedagogies Implements pedagogical approaches that are effective for Pacific learners. | 3.1 Recognises that all learners including Pacific are motivated to engage, learn and achieve. 3.2 Knows the importance of Pacific cultural values and approaches in teaching and learning. |