“Here’s what I know about teaching…as individuals, we don’t count for much. [There’s] not much we can do as individuals to change the way the world is. All we’ve got really are teaspoons of light. Here’s the deal. If we sprinkle a sense of community, [a] sense of possibility, you don’t need much. Carry your teaspoon carefully. Use it wisely. Recognise that out of all the things that you do with your young people, sprinkling light will be the most important thing that you do”.

Peter O’Connor (personal communication, 06 Jan 2021)

Imaginative Pedagogy – Peter O’Connor

Wed 06 Jan 2021

Walking alongside/with our students

Peter O’Connor invited us all to sit in a large circle. The instructions were: “walk with purpose” for about 30 seconds; stop on his command; then greet each other. He changed the greeting every-time i.e. Māori wave, Irish nod, English ‘avoid,’ and then Canadian ‘oh sorry.’ At this point, he is controlling what he calls the “rhythm” of our class. He switched things up by asking us to stop and go when he does. The goal was for everyone to stop at the same time, without any lag. We gradually began stopping at the same time. We were then put into groups.

What I learned and will take into my classroom:

- Respond to the “rhythm” of the class: “Every class you go into has a different rhythm, and your job as a teacher is to find that rhythm, help shape the rhythm, help move the rhythm of the class. Make it so that it’s an inclusive rhythm so that others can feel that they can join it [rhythm]” (personal communication, 06 Jan 2021). But he does caution us to still find our own path, not follow others but rather to engage with others. This is what Bishop and Berryman means when he talks about responsive ability (2009). This is also one of Timperley’s (2013) criteria of what constitutes an “adaptive expertise.”

- Build a sense of community: I realised that I was relying on those around me to determine when I stopped. I learned to use what he called my “sense of community” (personal communication, Jan 06, 2021). We learn, he said, by using our senses. For Peter, “the most powerful sense you have in your classroom is a sense of community.” Feeling that you are not an individual, you are not alone, but you belong alongside others. According to Bishop (2019), creating an extended family-like context is the necessary condition within which to create meaningful interactions with students. The apparatus on effective teaching practices all agree that promoting collective-efficacy is synonymous with improved student outcomes (see references).

- Success is measured by what we give: What does success look like for Peter? It is not traveling the world, it is not having flashy things, it is not having a high-paying job, but success is measured by what we give – a valuable lesson his father taught him. A successful teacher is a giving teacher: “teaching means being a servant for the children you work with [and for]” (personal communication, 06 Jan 2021).

- Imagination is what makes us fully human: teaching, for Peter, is the art of “making humans more fully human” (personal communication, 06 Jan 2021). Having imagination, Peter states, means having the ability to re-imagine the world. That is what makes us “fully human.” Peter emphasised that there is no better way to do this than by “warming up their [the student’s] imagination.”

“As teachers, we must model how we would like our students to be like to do this. For our students to be fully human, we must be fully human too.”

Peter O’Connor (personal communication, 06 Jan, 2021)

- Teach our students to re-imagine the world: “By killing the imagination, our schools are not training our students to re-imagine the world. We are training them for the world,” Peter said (personal communication, 06 Jan 2021).

- Ignore school deficit conversations: he urges us to be the Sisyphus of our schools. We must be resilient in our sense of social responsibility to our kids by continuing to push the boulder [the student] up the hill [of impossibility] for however long it takes. We must ignore those deficit conversations with teachers who, like the evil entity on our shoulders, coaxes us to “just give up pushing that [boulder], that’s not your job. Be just like us and let it go” (personal communication, 06 Jan 2021).

The Cloth of Torn Dreams Dialogue

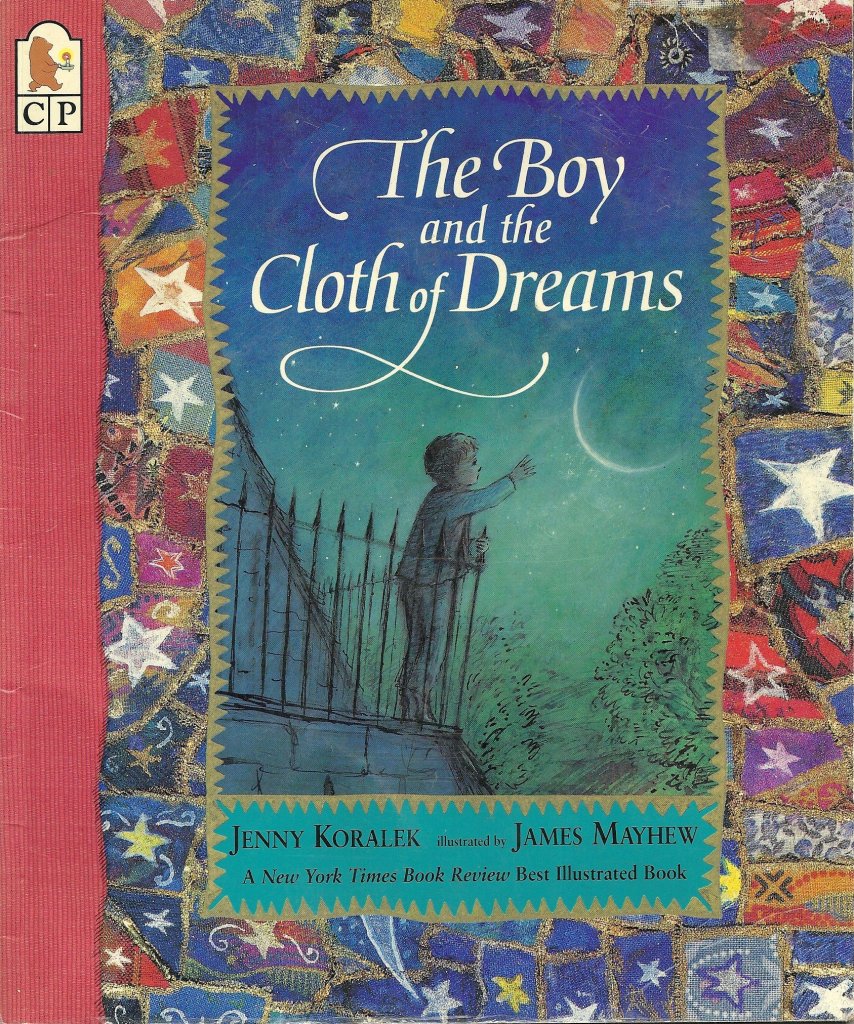

Every minute in Peter’s lesson was spent learning. The whole lesson was based around how to be imaginative in our teaching practice. He taught us how to creatively teach by teaching us creatively. He does this by warming up our imaginations. While we are rubbing our hands together he asks us to think where we last held them. He then takes the first line from The Boy and the Cloth of Dreams storybook (he changes the protagonist to a little girl) and begins thus:

“There was a little girl who woke up in the morning, and when she woke up, she

Peter O’Connor (personal communication, 06 Jan, 2021)

saw that her cloth of dreams had been torn. I wonder what kind of story this is…?” (he lets the question hang in the air while the class hums into discussion)

What I learned and will take into my classroom:

- Be the teacher that lends their cloth of dreams: This experience taught me that teaching to the North-West (Bishop, 2019) is possible. Peter compares the torn dream cloth to our students’ possibilities and dreams. He allows us to imagine what it would be like for our students if their dream cloth had been torn. What would we do? Peter emphasises that it is our vocation as teachers to walk alongside them while going through these changes. Would we restore it? While it is being restored, Peter urges us to be the teachers that loan our dream clothes to them while it is being repaired. How would we fix it? Peter’s answer is, we do it together, which brings me to my next lesson learned.

- Teach with your students not to them: Peter demonstrates how to do “collaborative storying” (Bishop, 2019) by using a story as a catalyst to co-construct a curriculum with, rather than for the students. Just as Bishop (2019) used Shell Hunter by Carl Geren (p.119-122), Peter used the first line from The Boy and the Cloth of Dreams by Jenny Koralek as a starting point for his lesson and allows the class to re-imagine or ‘re-story’ the rest of it by asking empowering questions.

- Ask empowering closed questions: Peter models how closed questions can be empowering questions. He asks closed questions like “would you like to help?” and “do you have one?”. By doing so, he has shifted the power from teacher to student. Peter has created a context where interaction between teacher and student becomes a collaborative and co-constructing “rhythm,” so to speak (Bishop 2005 & 2019). The children are encouraged to bring ‘who they are’ to the learning interactions in complete safety; student’s prior knowledge is accepted and legitimised. This way, learning is undertaken on terms understandable and relatable to the learners.

- Work with what your student’s already know: for re-storying or co-construction to work, I must work with what’s already known my students. Peter is what Timperley (2013) would call an “adaptive expertise”. An adaptive expertise is someone who is an expert at “developing a relationship in which teacher and student assume joint responsibility and agency for learning, and developing strategies for understanding students’ conceptions and misconceptions as a starting point for teaching” (p.32). Peter prefers to not know for “there is nothing more exciting for a teacher than not knowing what will happen next” (personal communication, 06 Jan 2021). For example, Peter would never have imagined mixing the ingredients for the thread in a cloud bowl.

- Demand critical thinking: there is a difference between facilitating and co-creating a story. At no one time does Peter lower his expectations. He questions and probes to allow the children to think critically. This is also one of Delpit’s “cheating” methods he suggests for teachers to use in order to “cheat the [school] system” (2006, p.225). Make no mistake, Peter does not facilitate the story-making process, but instead, he is a co-writer.

- Give students agency over their learning: through storytelling, Peter models and encourages agentic thinking (Bishop & Berryman, 2009) by giving the students self-determination and responsibility for their story, thereby over their learning. He sets-up this agentic and all-encompassing context by asking a “genuine question” (personal communication, 06 Jan 2021).

- Don’t ask questions you already know the answers to: “Agency is killed by asking questions you already know the answer to” (personal communication, 06 Jan 2021).

- Laugh: “laugh with your children, for them, about them, and with them. Laughter is not a laughing matter” (personal communication, 06 Jan 2021).

- Sprinkle a teaspoon of light on our students: “recognise that out of all the things that you do with your young people, sprinkling light will be the most important thing that you do” (personal communication, 06 Jan 2021).

Standards and Competencies

I could link some of the relevant parts of the Tātaiako competencies to his lesson. The reason he is at student teacher level is because his lesson was about teaching to a diversity of students, with diverse backgrounds and abilities, not a specific ethnic-group.

| Standard / Competency | A student teacher |

| Standard 4: Learning-focused culture Develop a culture that is focused on learning, and is characterised by respect, inclusion, empathy, collaboration and safety. | – Develop learning-focused relationships with learners, enabling them to be active participants in the process of learning, sharing ownership and responsibility for learning. – Foster trust, respect, and cooperation with and among learners so that they experience an environment in which it is safe to take risks. – Demonstrate high expectations for the learning outcomes of all learners, including for those learners with disabilities or learning support needs. – Create an environment where learners can be confident in their identities, languages, cultures and abilities. – Develop an environment where the diversity and uniqueness of all learners are accepted and valued. |

| Tātaiako: Whanaungatanga Actively engages in respectful working relationships with Māori learners, parents and whānau, hapū, iwi and the Māori community. | – Can describe from their own experience how identity, language and culture impact on relationships. |

| Tātaiako: Manaakitanga Demonstrates integrity, sincerity and respect towards Māori beliefs, language and culture. | – Values cultural difference. – Demonstrates an understanding of core Māori values such as: manaakitanga, mana whenua, rangatiratanga. – Is prepared to be challenged, and contribute to discussions about beliefs, attitudes and values. |

| Tātaiako: Tangata Whenuatanga: Arms Māori learners as Māori – provides contexts for learning where the identity, language and culture (cultural locatedness) of Māori learners and their whānau is armed. | – Knows about where they are from and how that informs and impacts on their own culture, values and beliefs |

| Tātaiako: Wānanga Participates with learners and communities in robust dialogue for the benefit of Māori learners’ achievement. | – Demonstrates an open mind to explore differing views and reflect on own beliefs and values. – Shows an appreciation that views which differ from their own may have validity. |

| Tataiako: Ako Takes responsibility for their own learning and that of Māori learners | – Can explain their understanding of lifelong learning and what it means for them. Positions themselves as a learner. |

| Tapasā Turu 1: Identities, languages and cultures Demonstrate awareness of the diverse and ethnic-specific identities, languages and cultures of Pacific learners. | 1.1 Understands his or her own identity and culture, and how this influences the way they think and behave. 1.2 Understands the importance of retention and transmission of Pacific identities, languages and cultural values. |