By Pasifika people, for Pasifika people

PASS motto

Mon 23 Nov – Thurs 03 Dec 2020

During weeks 2-4 of our Summer Intensive, Te Ahitū was divided by Kāhui Hāpai, with each group spending three weeks at a different partner school. Half of us remained in Auckland. The other half was split between Rotorua and Whangārei. Within our schools, we were divided into small teaching teams within our Kāhui Hāpai, where we got to observe classes, engage with the students, and then teach with our teams. Our Kāhui Hapai, Toki, spent our in-school residential at Pacific Advance Secondary School – known as PASS – located in Ōtāhuhu, Auckland, where I was put into a team with the incredible Richard O’Malley and Shirley Tolai.

My PASS experience has greatly impacted my learning as a beginner teacher, some of which I will share below. Below are my observations of the school and the things I believe are why their students excel in their educational achievements.

What is unique about PASS?

- Come up with a class motto together with all my classes

Falefatu and his wife Parehuia Enari responded to an urgent call from their community here in Tāmaki Makaurau – the Pasifika students in Tāmaki Makaurau needed them. So they left their paradise in Te Tai Rāwhiti (East Coast) to set up a new kura (school) in Ōtāhuhu for the Pasifika youth in Auckland.

Opening the doors to PASS was not without its challenges. They had their belief in God, their vision, a dilapidated building, and a deadline of four months. They worked tirelessly to build their kura up from scratch—the result, a unique and culturally responsive school environment where students are currently thriving.

What is unique about PASS? PASS is the first ‘Pasifika mo le Pasifika – By Pacific people, for Pacific people’ secondary school in Aotearoa, New Zealand (see PASS website). For me, this captures everything that PASS is. This, along with their school values, the Fono Fale model forms the basis of their school curriculum and teaching philosophy.

The Power of God

- Create a safe and inclusive environment in my classroom for students of differing beliefs and cultural backgrounds (e.g., a neutral karakia students can put their values into, or we can write our class karakia together)

- Create a restorative process with students (similar to Anga Talavou)

PASS is a transitional school for many students, some of whom recently immigrated from their homelands in the Pacific. At PASS, faith permeates every aspect of school life. Every morning is greeted with pese (praise) and lotu (worship), which is not too dissimilar to how many schools in the Pacific start their day.

Among Delpit’s (2006, p.230) lists of instructions to teachers was to foster a sense of the student’s connection to the community, to something greater than themselves. I saw, first hand, the power of believing in something greater than themselves, of believing in God, had propelled the students at PASS to show accountability.

The week before we arrived at PASS, the second floor of the Junior block had been vandalised. They had trashed it. Parehuia and Falefatu took us into this room to see the damage that was done there. E fofo e le alamea le alamea – the solutions for our issues lie within our communities. Their answer to the vandalism was their mala’e restorative practice model (anga talavou), a culturally responsive process designed by the school to handle this.

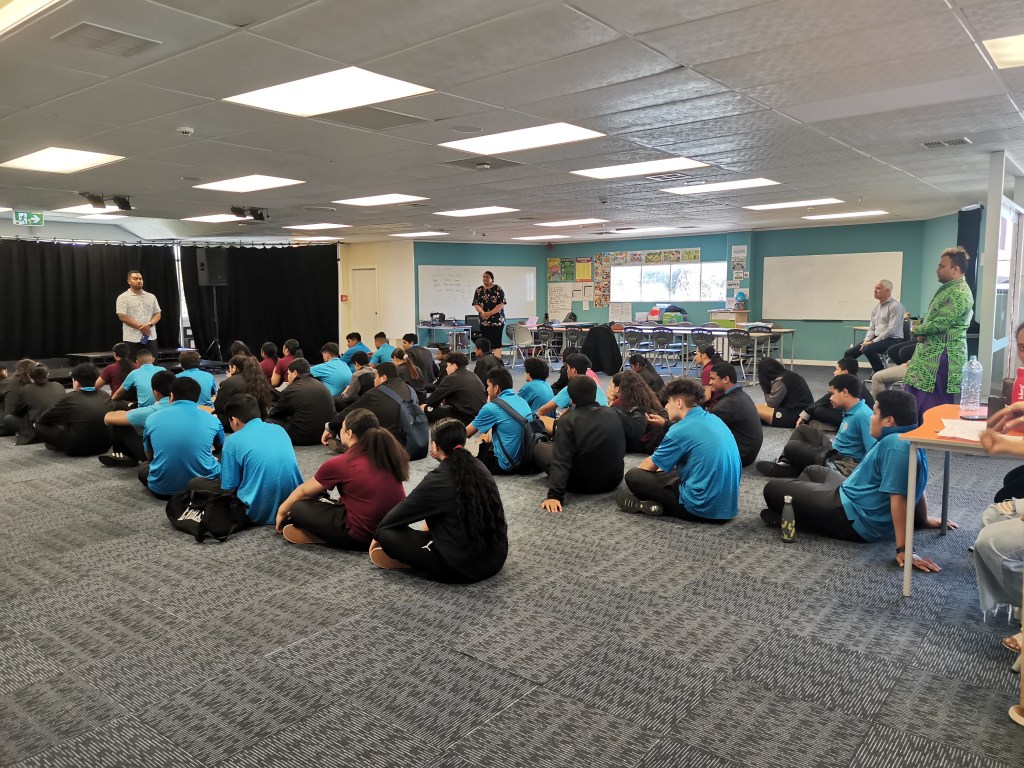

Their first response to the vandalism of their school property was to pray. Their second response was the implementation of the mala’e restorative practice stage of their school behavioural management program. The process involved a whole school assembly where the students (70 junior school students) sat in a ‘U’ formation; the girls sat in the middle flanked by the boys. Tinā and Tamā sat in front of the cohort cross-legged. Tamā initiated the dialogue by using his ‘pooh in the hot-pot’ analogy. He likened the issue to someone poohing in the hot-pot of kai that a Chinese family had lovingly made for them.

Tinā elaborated and made explicit what the issue was. She gave the students an ultimatum. The students were given until the end of the pese and lotu for students to step forward and inside the ‘U’ formation if they had done something that Tinā and Tamā would not condone. If they did not ‘own-up’ to their misdeeds, Parehuia warned they would do it Pālagi-style – stand-down, suspension, or even worse, exclusion.

Almost a quarter of the student body stepped into the ‘U’ formation. Their strong belief in God and connection to their nu’u and aiga at PASS had propelled these students to step forward and be accountable for their actions.

For students at PASS, lotu and pese provide much-needed energy for them to learn; it sets them up for a good day ahead. It provides them with hope. After observing and having talanoa with the PASS students, I understood that lotu and pese meant so much. When I asked the students how lotu helps with their learning, replies included: “it gives me energy,” “it gives me hope,” “it sets my day up for learning” (personal communication, 26 Nov 2020).

Coming from a holistic and polytheistic belief system of Atua and tīpuna Māori, I found the religious aspect of PASS quite confronting at first. Used as a tool for colonisation and land alienation in the early settlement of Aotearoa, there is still a deep mistrust among my people of the church. However, upon reflection, I realised that faith connects these otherwise disconnected students to their homeland, to their tuakiritanga (identity).

I can relate to this, and so can many of our disenfranchised Māori youth. Faith connects our Pasifika students to their identity and language, just as culture and language connect our Māori students to their identity. This experience prompted me to ask myself: how, then, can I create a safe and inclusive environment in my classroom for all my students of differing beliefs and cultural backgrounds?

The Power of Community

- Create a nu’u where students can feel they belong (e.g., class villages with an elected chief)

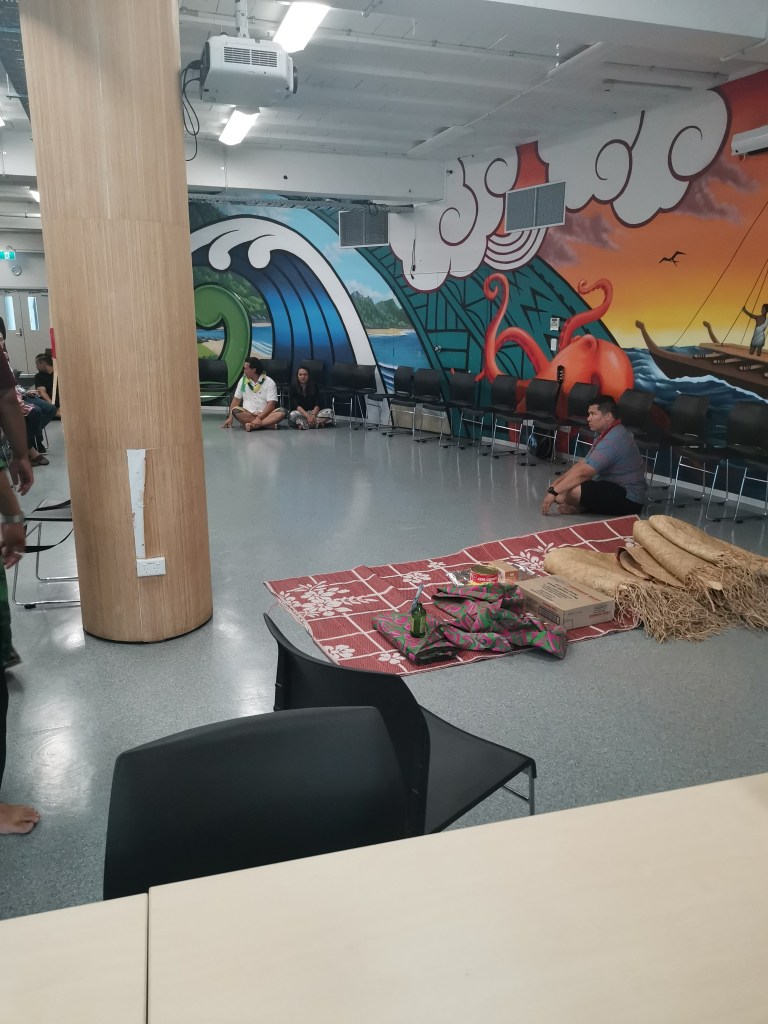

PASS is unique in how they address and treat each other. The only equivalent to PASS are our Kura Kaupapa Māori (Māori Immersion) Schools, where staff and students treat each other as one big whānau (see Milne, 2016). Similarly, aiga (family) and nu’u (village) are a significant part of PASS culture that is underpinned by core fa’a Samoa values of tautua (service), fa’aaloalo (respect), and alofa (love).

I witnessed all three values being displayed by the students on my first day. My first encounter with the students was when we entered the dining hall on our first day. Upon entry, the doors were held open by students (fa’aaloalo) who beamed at us with their welcoming smiles (alofa) and served us a delicious kai (tautua) that they cooked with Aunty Mele.

PASS engenders a village, which in turn engenders belonging. The school operates under the maxim that ‘it takes a village to raise a child.’ PASS is a village where teachers are referred to as ‘Aunty,’ and ‘Uncle’ and the co-principals are called ‘Tinā’ and ‘Tamā’ – Samoan for mother and father. It is not a school of students and staff, but a village consisting of village parents, brothers and sisters, uncles and aunties, of a tinā and tamā. PASS is a aiga.

Research has shown and proven that collective-efficacy is consistent with positive outcomes. “The most effective activities that educators can engage in are those that implement collective efficacy” (Bishop, 2019). According to Bishop, this needs to be present from the get-go. Creating an extended-like environment is the necessary condition for building self-determining and confident students at Tāmaki College. I hope to create my own little PASS-room.

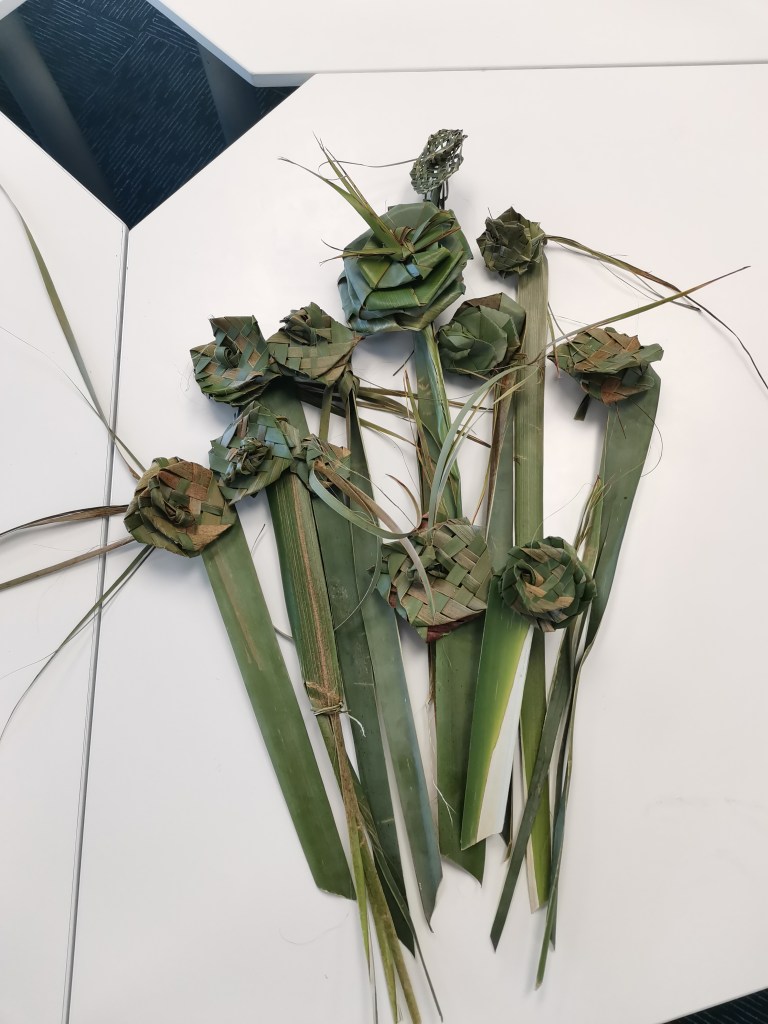

Putiputi made by students with myself and Aunty Hana. Photo: Author (2020).

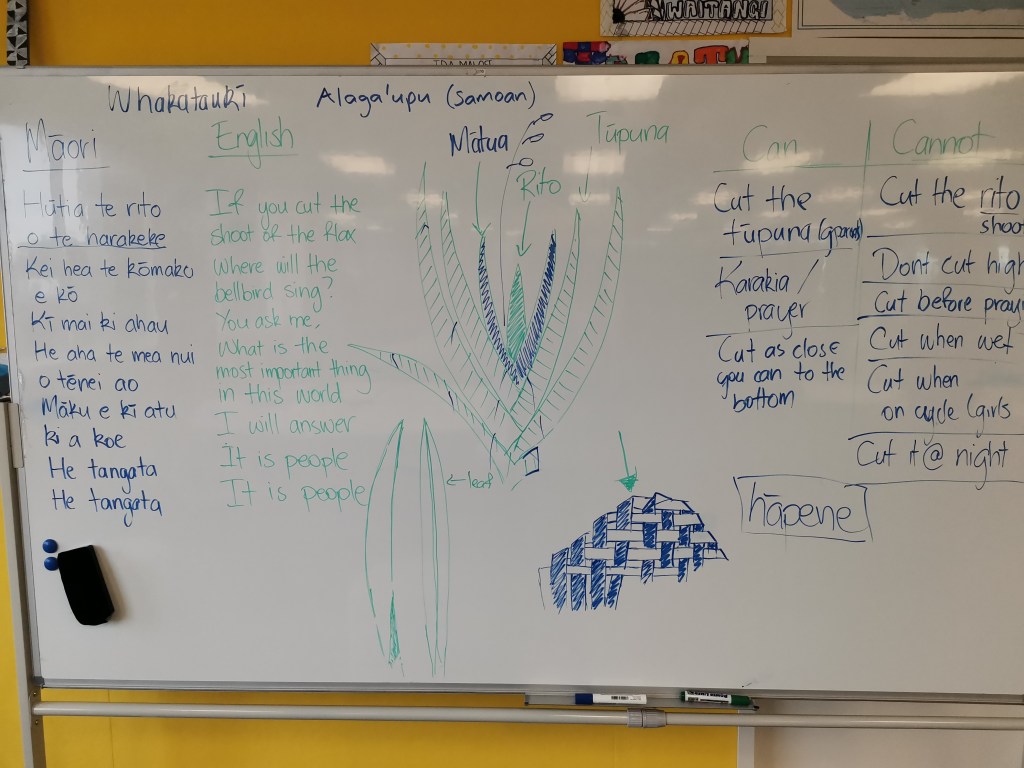

Our lesson about harakeke. Photo: Josh Tagaloa (2020).

The Power of Cultural Identity

- Create a cultural classroom where ‘va’ between student and teacher are cared for and maintained (e.g., teu le va, regular talanoa or wānanga)

- Incorporate Crossfit/conditioning in my lessons (similar to Tū Tangata)

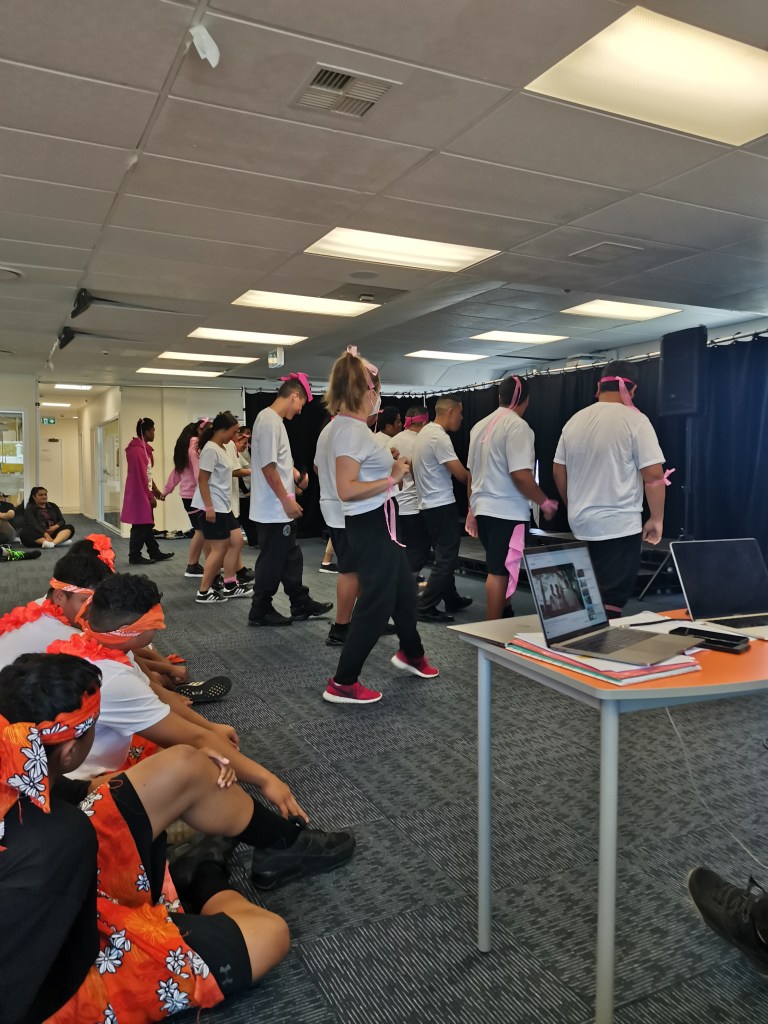

At PASS, they are acknowledged as culturally-located individuals. Students are encouraged to bring their Moana-nui-ā-Kiwatanga or their ‘Polynesian-ness’ to school. When Māori and Pasifika enter mainstream schools, they often have to leave their fa’a Pasefika ways outside the school gates. However, at PASS, the Pasefika way is the starting point of each day through Tū Tangata (physical conditioning), the sharing of food, family pese (praise), lotu (worship), and talanoaga (family discussions/encouragement). It was also a part of our whakatau process.

During our whakatau, a young man delivered a speech in his mother tongue of Samoa. I got goosebumps watching and listening to him. He reminded me so much of our Kura Kaupapa Māori students. You could see he was still very much connected and rooted in his Hāmoatanga. Mose, a Matai and a member of our Toki aiga, stood to respond with equal elegance and humility.

Like Kia Aroha College (Milne, 2016), PASS center their school on their learners’ uniqueness and cultures. Research has shown that pride of identity and culture are synonymous with improved tauira outcomes (see Milne, 2016). I must create what Fehoko (2015) calls a “cultural classroom” situation, where all learners feel secure in their own identities. Wherever identity is affirmed, nurtured, and maintained, educational achievements are sure to follow.

PASS is not too dissimilar to Kia Aroha, where the curriculum is centred on their students’ identities and cultures. Kia Aroha, like PASS, operates as one big whānau (Milne, 2016). Both schools recognised the need to help our Māori and Pasifika youth in Tāmaki, particularly South Auckland, to teu le vā in Palagi and Māori spaces and Palagi in Māori and Pasifika (Anae, 2010), as partners of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. To teu le vā in these spaces is no easy task, according to Anae, but it can lead to positive outcomes if all stakeholders have the “will” and the “spirit” (p.13):

“This is not to say that to teu le vā in all one’s relationships is doable, nor an easy process. More often than not, it is complex, multi-layered, and fraught with difficulties. But if all parties have the will, the spirit, and the heart for what is at stake, then positive outcomes will be achieved.”

Want to know more about PASS? Click here to read their vision and mission statement for their Pasifika learners.

Standards and Competencies

| Standard / Competency | A student teacher |

| Standard 1: Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership Demonstrate commitment to tangata whenuatanga and Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership in Aotearoa New Zealand. | – Understand and recognise the unique status of tangata whenua in Aotearoa New Zealand. – Understand and acknowledge the histories, heritages, languages and cultures of partners to Te Tiriti o Waitangi. – Practise and develop the use of te reo and tikanga Māori. |

| Standard 4: Learning-focused culture Develop a culture that is focused on learning, and is characterised by respect, inclusion, empathy, collaboration and safety. | – Develop learning-focused relationships with learners, enabling them to be active participants in the process of learning, sharing ownership and responsibility for learning. – Create an environment where learners can be confident in their identities, languages, cultures and abilities. – Develop an environment where the diversity and uniqueness of all learners are accepted and valued. |

| Tātaiako: Whanaungatanga Actively engages in respectful working relationships with Māori learners, parents and whānau, hapū, iwi and the Māori community. | – Can describe from their own experience how identity, language and culture impact on relationships. |

| Tātaiako: Manaakitanga Demonstrates integrity, sincerity and respect towards Māori beliefs, language and culture. | – Values cultural difference. – Demonstrates an understanding of core Māori values such as: manaakitanga, mana whenua, rangatiratanga. – Shows respect for Māori cultural perspectives and sees the value of Māori culture for New Zealand society. – Is prepared to be challenged, and contribute to discussions about beliefs, attitudes and values. – Has knowledge of the Treaty of Waitangi and its implications for New Zealand society |

| Tātaiako: Tangata Whenuatanga: Arms Māori learners as Māori – provides contexts for learning where the identity, language and culture (cultural locatedness) of Māori learners and their whānau is armed. | – Knows about where they are from and how that informs and impacts on their own culture, values and beliefs |

| Tātaiako: Wānanga Participates with learners and communities in robust dialogue for the benefit of Māori learners’ achievement. | – Demonstrates an open mind to explore differing views and reflect on own beliefs and values. – Shows an appreciation that views which differ from their own may have validity. |

| Tataiako: Ako Takes responsibility for their own learning and that of Māori learners | – Recognises the need to raise Māori learner academic achievement levels. – Is willing to learn about the importance of identity, language and culture (cultural locatedness) for themselves and others. – Can explain their understanding of lifelong learning and what it means for them. |

| Tapasā Turu 1: Identities, languages and cultures Demonstrate awareness of the diverse and ethnic-specific identities, languages and cultures of Pacific learners. | 1.1 Understands his or her own identity and culture, and how this influences the way they think and behave. 1.2 Understands the importance of retention and transmission of Pacific identities, languages and cultural values. 1.3 Is aware of the diverse ethnic-specific differences between Pacific groups and commits to being responsive to this diversity. 1.4 Understands that Pacific world-views and ways of thinking are underpinned by their identities, languages and culture. |

| Tapasā Turu 2: Collaborative and respectful relationships and professional behaviour Establishes and maintains collaborative and respectful relationships and professional behaviours that enhance learning and wellbeing for Pacific learners. | 2.1 Understands his or her world-views and ways of building relationships differ from those of Pacific learners. 2.2 Understands that there are different ways to engage and collaborate successfully with Pacific learners, parents, families and communities. 2.3 Is aware of the importance of respect, collaboration and reciprocity in building strong relationships with Pacific learners, their parents, families and communities. |

| Tapasā Turu 3: Effective Pacific pedagogies Implements pedagogical approaches that are effective for Pacific learners. | 3.1 Recognises that all learners including Pacific are motivated to engage, learn and achieve. 3.2 Knows the importance of Pacific cultural values and approaches in teaching and learning. 3.3 Understands that Pacific learners learn differently from each other, and from their non-Pacific peers. 3.4 Understands the aspirations of Pacific learners, their parents, families and communities for their future and sets high expectations. |