Tues 5 Jan – Thurs 7 Jan 2021

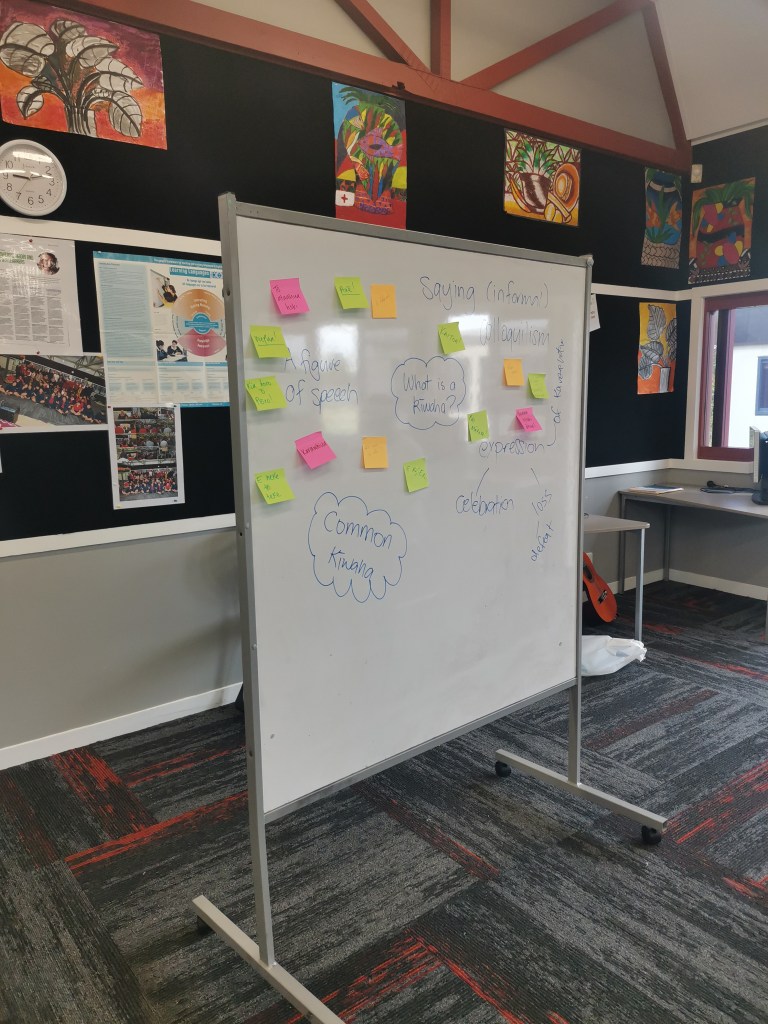

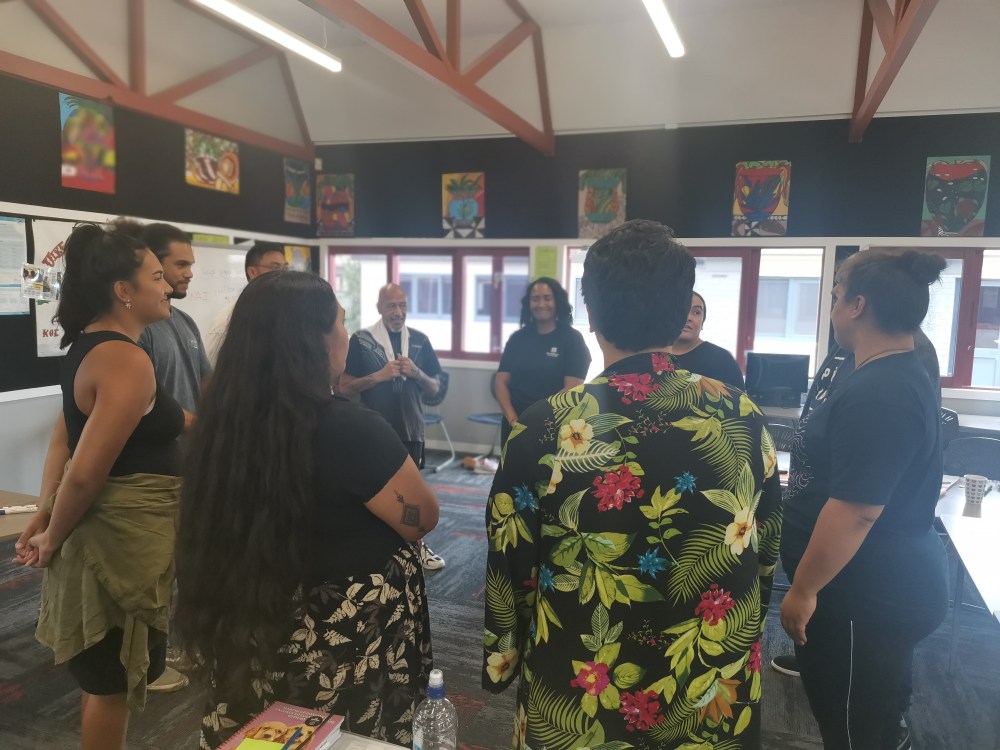

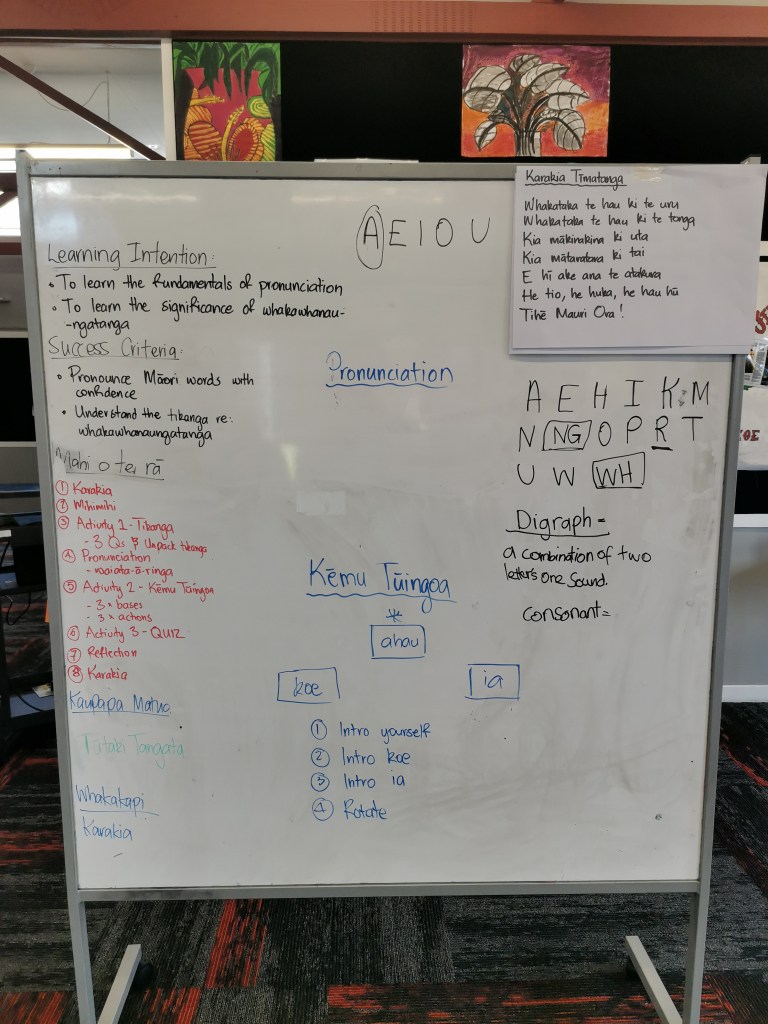

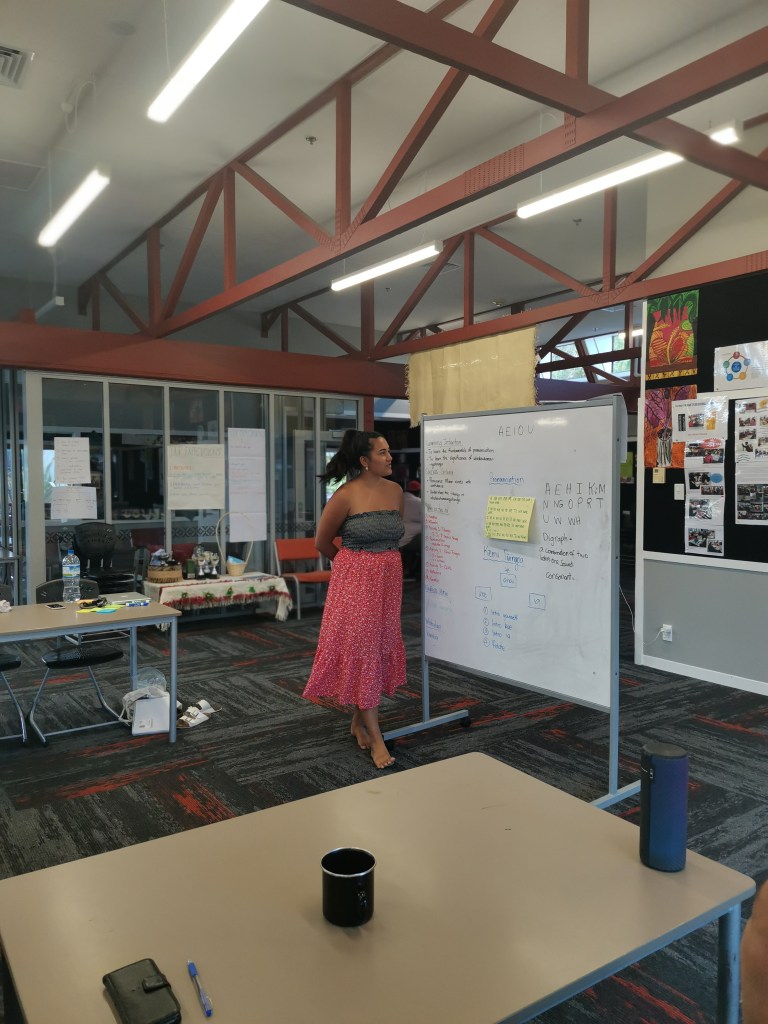

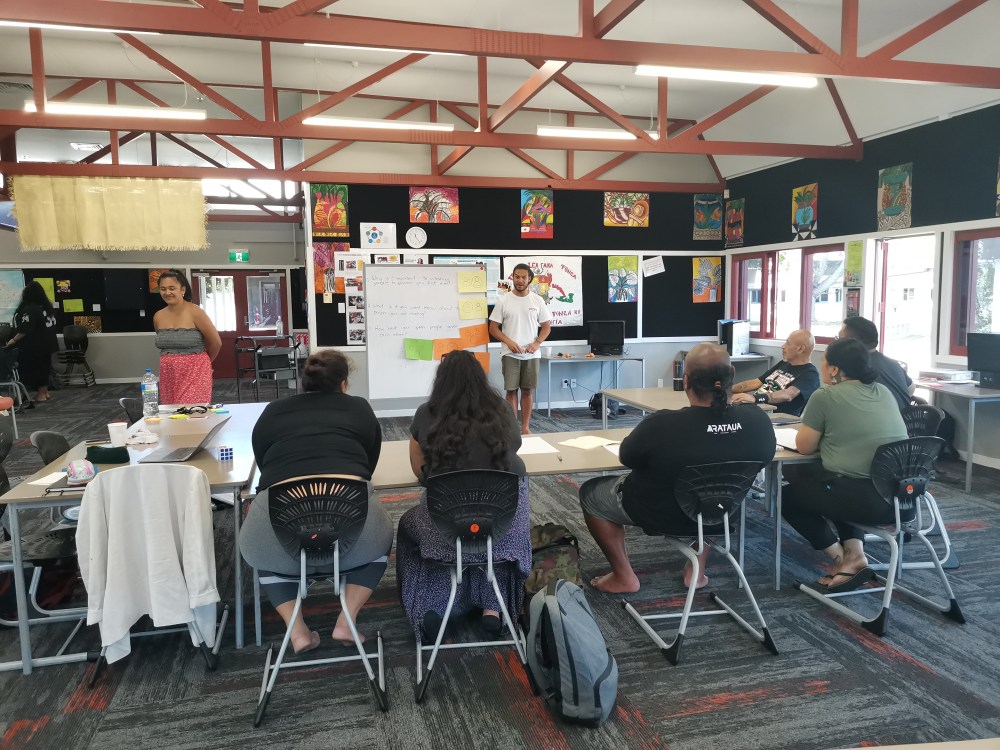

During our Kete Week 1, we were separated into our respective Kāhui Ako, i.e., Te Reo Māori. We were then put into groups of three or four. Our small groups were tasked with planning and teaching four lessons to each other. These lessons made up the first, middle, and end of our Course Designs (or Unit Plans).

Our Unit Plan

We created this unit on the premise that more and more speakers are using te reo Māori to communicate and build relationships with others (Ministry of Education, 2009, p.13). This unit was designed for a multi-ethnic Year 9 classroom. Each lesson is a scaffold to help build the students confidence and understanding of conversing in te reo Māori when meeting people, hence the title Tūtaki Tangata (meeting and greeting people).

Why this experience impacted me:

This learning experience had a significant impact on my confidence and growth as a beginner teacher. I feel I am better prepared for the year to come.

What I learned and will take into my classroom:

- Self-efficacy provides the confidence needed for teaching: I felt that I needed to make sure my own foundations were strong first before helping others build theirs. I felt reassured when Sleeter (2008) had found that this is the typical developmental process of a beginner teacher: “Learning to teach is a developmental process in which the novice typically progresses from concerns about self, to concerns about students and their learning” (p.571).

- Planning sets you and your students up for success: I understood that being prepared sets myself and my students up for success. According to Jono Smith, it is one of the three ingredients for a great teacher presence. When students were asked about how teachers could be useful in Bishop’s Culture Speaks, they answered:

“Don’t start thinking about what you are going to teach us when we walk in the room. Get prepared.”

Bishop, 2006

- Don’t get caught up in the little things: I learned a lot about myself over those three days, as a person and as a developing teacher. I realised that I am a stickler for details, for one. Brian, Tiana, and I spent up to 3 hours zoom messaging every night to plan lessons for the following day. I would hammer them for all the finer details. No stone was left unturned.

- Let questions hang and come back to it later: in one one of our feedback-feedforward sessions, Moana-Aroha advised me to let my questions hang to allow learners to answer them. I was being what Timperley calls a “routine expert” (2013). I had done what Peter O’Connor had instructed us not to do. On my own, I essentially took away my learners’ agency by asking questions for which I already had answers prepared. Knowing what I know now, I can do better. I can be better.

- Have heaps of games/activites in your arson:

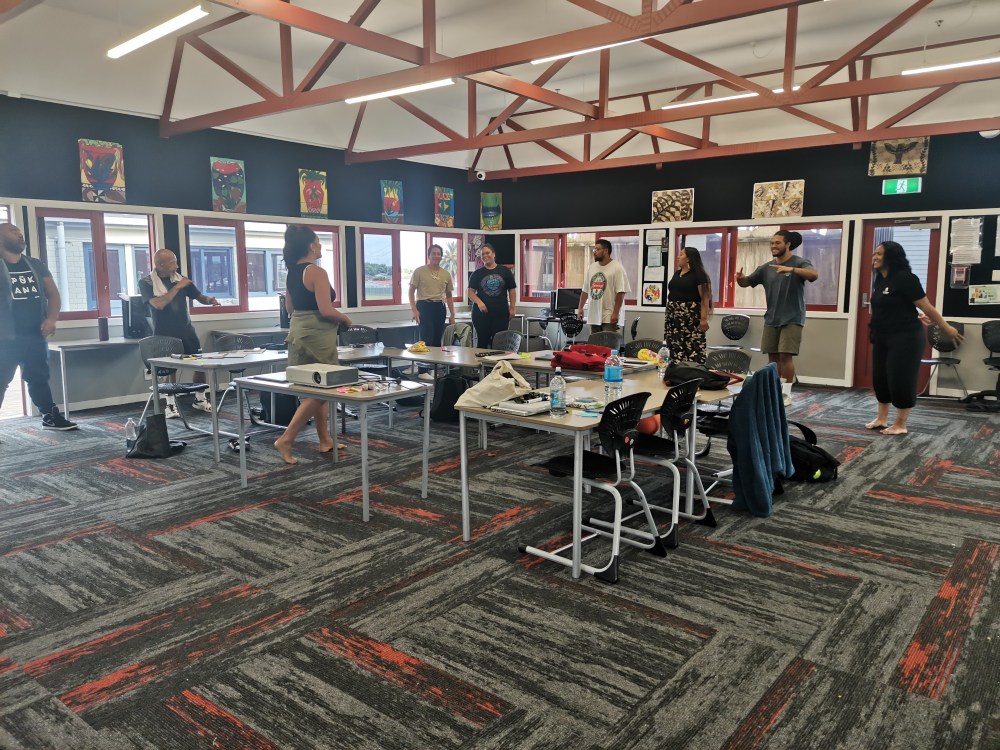

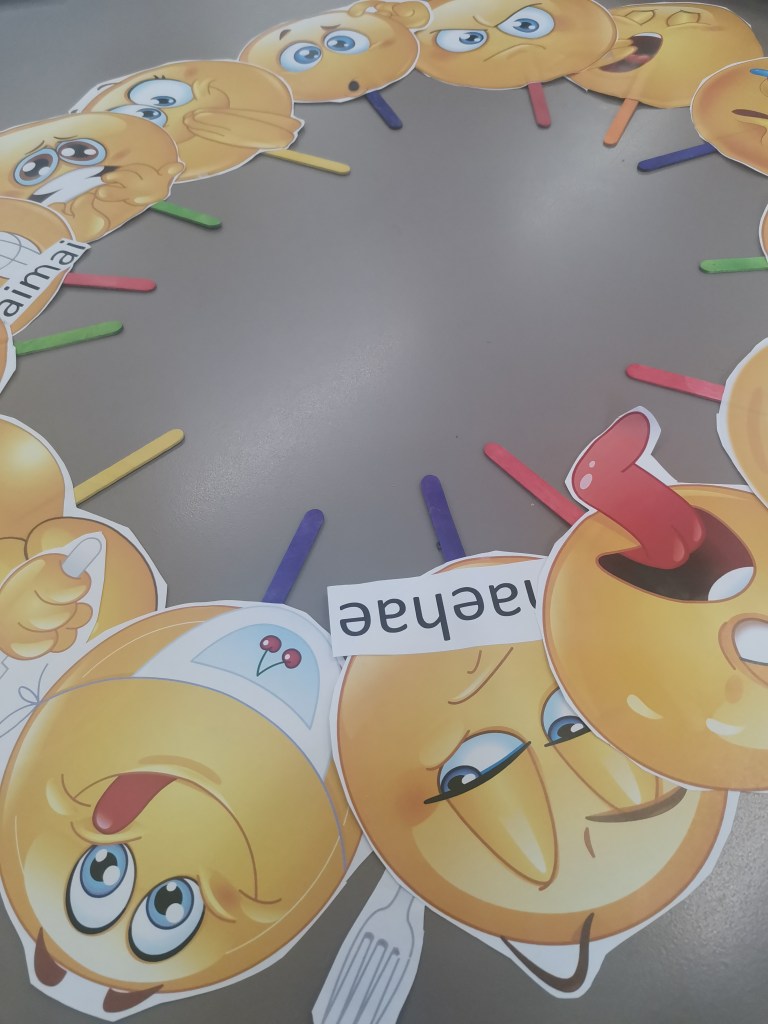

- Pepeha game: one of my highlights was the pepeha game. This would be a fantastic game to teach about pepeha, marae, and whānau. This game is similar to the number game where you walk around, and then the caller yells out a number, and you find people to make up that number. In the pepeha game, numbers are replaced by pepeha terminologies such as maunga, awa, rangatira, waka, and iwi. Rangatira is one person holding three fingers up behind the head to appear like a plume. Maunga requires two people to create a mountain peak by touching fingers. Awa involves three people to join hands and make wave-like motions. Waka is when four people row an imaginary canoe. Iwi is just five people joining hands. This would be a fantastic game to teach the vocabulary necessary to introduce a pepeha unit of work.

- Imaginary marae mapping: one of the groups got us to stand where our marae are located on an imaginary map of Aotearoa. Haramai tētahi āhua! I wish to take this idea and modify it by getting my students to paint large maps of Aotearoa, Samoa, and Tonga. This has the potential to be a collaborative and fun cross-curricular exercise. I can then use these to do the same activity, only with a real map.

- Hand actions and the alphabet song: I loved Tiana’s creative adaptation of the arapū Māori song. She paired everyone up and got them to come up with actions for their rārāngi pū. One group came up with hand actions for A HA KA MA NA PA RA TA WA NGA WHA, and the next group created hand actions for E HE KE ME NE PE RE TE WE NGE WHE, and so forth. Once completed, everyone sang the song using the hand actions they had come up with. I will be using this activity in my pronunciation lessons.

- Not every lesson has to be a gourmet lesson: I learned that every lesson does not have to be a gourmet lesson. Brian Enari puts it eloquently when he said that: “some lessons will be gourmet burgers while others will be cheese toasties…it’s still a feed” (personal communication, 06 Jan 2021). Looking at it from a sustainable perspective, he is correct. However, I struggle to reconcile my Aunty Sandra Hei Hei’s instructions to “always give your best kai to your manuhiri” with having to settle for less when planning my lessons. Maybe the solution is in Peter O’Connor’s wise instruction to “plan less and teach more” (personal communication, 06 Jan 2021). It is how I serve the dish, not what is on it.

- Instructional teaching is important: this experience also taught me that traditional ways of teaching has an important role in teaching. Nyra Marshall encouraged us to “always be explicit about what the students’ have learned and where they are going” (personal communication, 07 Jan 2021). I learned that as experts or as subject specialists, it is important to connect what our students are learning to how they are learning. Many pedagogical approaches I have studied so far have privileged the learner’s role at the expense of the teacher (Rata, 2017). We belong to an era where it is not good practice to be a “routine expert” (Timperley, 2013). When reading the literature on current effective teaching practices, a teacher can feel like their knowledge means no more and no less than a student’s. If this were the case, anyone could teach te reo Māori. According to Rata a student cannot acquire “epistemic ascent” (p.1005) with facilitation methods alone. Traditional transmission methods such as instructional teaching are essential to allow the student to achieve subject mastery. Rata argues that a modern individual is a rational individual. Rational knowledge is independent of context; it is symbolic and is generally inaccessible to the everyday child. Instructional teaching by a subject expert is required to connect these abstract concepts to the real world.

“Teachers really are cultural brokers who have the opportunity to connect the familiar to the unknown”

Delpit, 2006, p.226

- Designing and teaching this unit plan is an example of instructional teaching. Te Reo Māori is full of abstract and inaccessible concepts and language that only a specialist, like me, can materialise into a Course Design like this. Instructional teaching provides structure and organisation. It allows students to develop “subject ‘metacognition'” (Rata, 2017, p.1009). Teaching as instruction will enable students to make objective judgments, to think rationally about the knowledge being taught. For these reasons, I will be using both traditional and modern teaching methods to teach my students.

Feedback and Feedforward for our Unit of Work

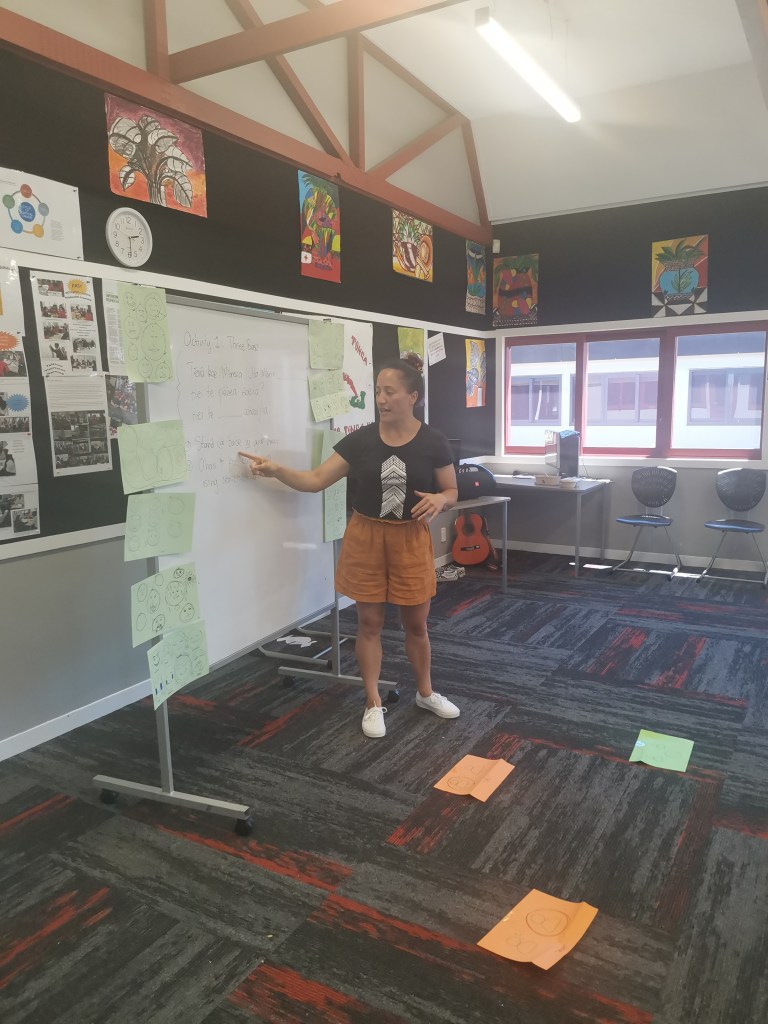

- Treat raupapa / rārangi mahi as a checklist: tick off the mahi as you go. That way, students who left and had just come back need to see where everyone is at, and it is also an excellent way to check-in on all the students’ learning.

- Do not end classes abruptly: leave ample time to wrap-up, pack-up, and do a karakia whakawātea.

- Use a variety of settling activities for the wrap-up and pack-up part of the lesson.

- Provide opportunities for students of all personality types to be able to engage: have options ready for shy students where tasks/activities involve presenting in front of the class.

- Set-up and then teach / scaffold:

- Meaning teach the language or new concepts/words and then ask the pātai (question).

- Teach the kupu and then do the exercise.

- Pitch to the appropriate level when designing your course while also still pushing the students.

- Read the room: especially when discussing new concepts like kīwaha and kīrehu.

- Be explicit about the success criteria and the assessment task: ensure that the success criteria of each lesson link well to the rubric of the assessment task.

- Teach what you intend the students to learn (learning intention): if it is your learning intention, teach that to the class to know they learned it.

- Choose smart success criteria that you know that a Year 9 student would achieve.

- Pair productive and receptive learning modes: Always pair the skill of ‘using’ (productive) with ‘understanding’ (receptive) when designing your lessons.

- Allow for peer-assessment opportunities: in the assessment tasks, create opportunities for peer-assessment and a teacher-assessment.

- Too much content: Do not try and squeeze too much content into an hour.

- Factor in means of measuring how the success criteria have been met in your course design:

- I could make it explicit to learners what they have learned by saying something like: “Today we learned about…”

- I could start with success criteria and plan lessons from there.

- Can do two exercises and ask one student a question on that exercise and if that student does not get it, then try another student, and if that student has not got it, then most likely everyone hasn’t got it.

- See the board set-up strategy below for more ideas.

- Board set-up:

- Do the board in bilingual (i.e., reflection / huritao). That way, you won’t have to translate the words as it is already on the board: “use every opportunity as a learning opportunity” (Moana Aroha said in her feedforward to us).

Hei Whakaarotanga

In one of the other group’s classes, I questioned the use of the kupu ‘kāti.’ They used it to mean the command ‘stop,’ as in, stop at the lights. I felt it was used in the wrong context. It was explained that this is the suggested vocabulary aligned to the Achievement Object and curriculum level they were pitching to.

I understand the purpose of using these different kupu is to broaden the student’s vocabulary. I don’t feel that building vocabulary needs to be built into the Curriculum. This happens naturally over time anyway. I am a firm believer that our reo must be taught correctly and from the get-go. This is what Tīmoti Karetu means when he says, “ko te reo kia tika.”

Rauemi

The following are the resources that our team relied heavily on during those three days. We found them extremely useful.

Standards and Competencies

| Standard / Competency | A student teacher |

| Standard 1: Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership Demonstrate commitment to tangata whenuatanga and Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership in Aotearoa New Zealand. | – Understand and recognise the unique status of tangata whenua in Aotearoa New Zealand. – Understand and acknowledge the histories, heritages, languages and cultures of partners to Te Tiriti o Waitangi. – Practise and develop the use of te reo and tikanga Māori. |

| Standard 4: Learning-focused culture Develop a culture that is focused on learning, and is characterised by respect, inclusion, empathy, collaboration and safety. | – Develop learning-focused relationships with learners, enabling them to be active participants in the process of learning, sharing ownership and responsibility for learning. – Create an environment where learners can be confident in their identities, languages, cultures and abilities. – Develop an environment where the diversity and uniqueness of all learners are accepted and valued. |

| Tātaiako: Whanaungatanga Actively engages in respectful working relationships with Māori learners, parents and whānau, hapū, iwi and the Māori community. | – Can describe from their own experience how identity, language and culture impact on relationships. |

| Tātaiako: Manaakitanga Demonstrates integrity, sincerity and respect towards Māori beliefs, language and culture. | – Values cultural difference. – Demonstrates an understanding of core Māori values such as: manaakitanga, mana whenua, rangatiratanga. – Shows respect for Māori cultural perspectives and sees the value of Māori culture for New Zealand society. – Is prepared to be challenged, and contribute to discussions about beliefs, attitudes and values. – Has knowledge of the Treaty of Waitangi and its implications for New Zealand society |

| Tātaiako: Tangata Whenuatanga: Arms Māori learners as Māori – provides contexts for learning where the identity, language and culture (cultural locatedness) of Māori learners and their whānau is armed. | – Knows about where they are from and how that informs and impacts on their own culture, values and beliefs |

| Tātaiako: Wānanga Participates with learners and communities in robust dialogue for the benefit of Māori learners’ achievement. | – Demonstrates an open mind to explore differing views and reflect on own beliefs and values. – Shows an appreciation that views which differ from their own may have validity. |

| Tataiako: Ako Takes responsibility for their own learning and that of Māori learners | – Recognises the need to raise Māori learner academic achievement levels. – Is willing to learn about the importance of identity, language and culture (cultural locatedness) for themselves and others. – Can explain their understanding of lifelong learning and what it means for them. Positions themselves as a learner. |

| Tapasā Turu 1: Identities, languages and cultures Demonstrate awareness of the diverse and ethnic-specific identities, languages and cultures of Pacific learners. | 1.1 Understands his or her own identity and culture, and how this influences the way they think and behave. 1.2 Is aware of the diverse ethnic-specific differences between Pacific groups and commits to being responsive to this diversity. 1.3 Understands that Pacific world-views and ways of thinking are underpinned by their identities, languages and culture. |