What is a significant moment of learning?

Te Aho Arataki Marau mō te Ako i te Reo Māori (TAAM) and the NCEA assessment system is only serving to widen the learning gaps for some of our te reo Māori students in English-medium schools. The proposed changes to NCEA will do nothing to alleviate this issue. It does and will not promote an inclusive education for all ākonga. Somehow what initially was a curriculum that presented kaiako with flexible guidelines to design their learning content and assessments has now become Te Korokoro o Te Parata or The Throat of Te Parata. Te Korokoro o Te Parata is the great whirlpool summoned by Ngātoroirangi, the tohunga on the Te Arawa canoe en route to Aotearoa, to swallow up Tamatekapua who had seduced his wife Kearoa. Like the great whirlpool invoked by Ngātoroirangi, TAAM and NCEA are spiralling into a destructive vortex that is killing our students love for learning the language of this land, which will impact negatively on our attempts to revitalise our beloved national language.

How did I come to this moment of learning?

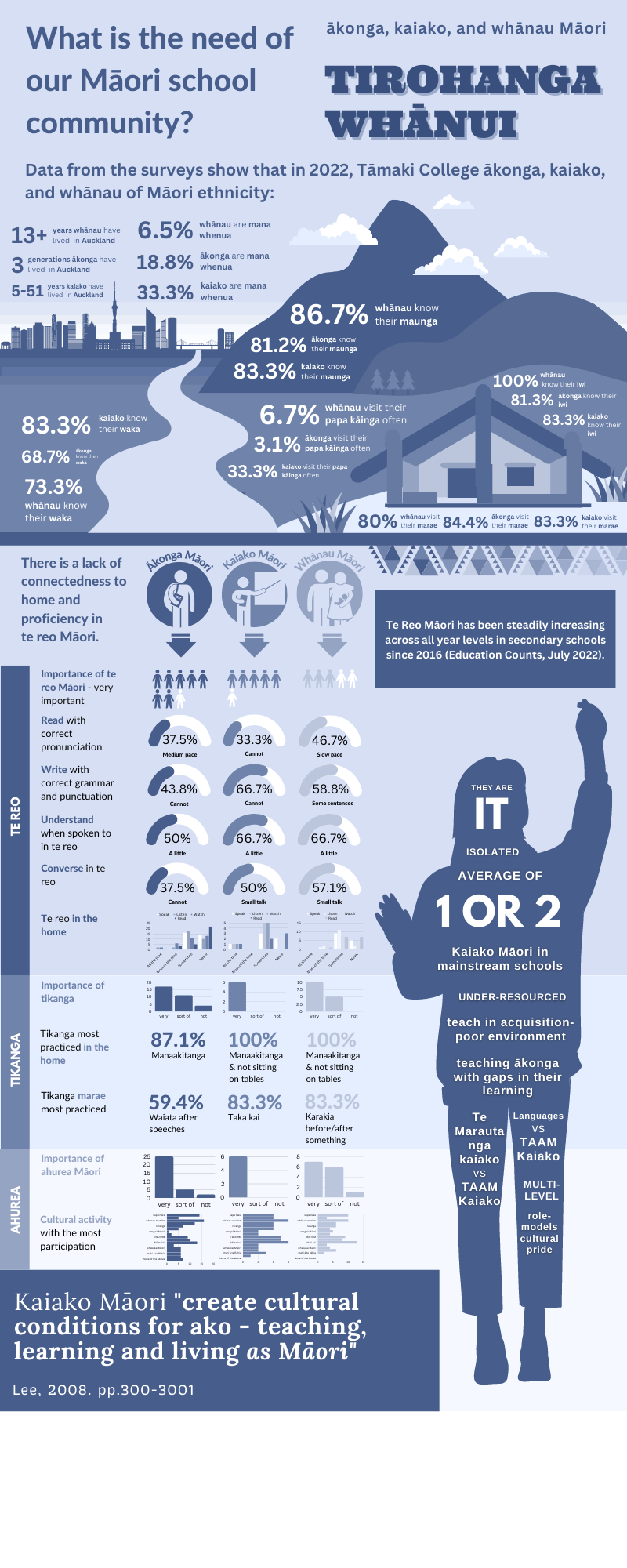

My ākonga are not prepared to meet the criteria of the NCEA achievement standards and levels of progression in TAAM. This has been exacerbated by the impacts of Covid-19 and the whole nation lockdowns. When considering the te reo Māori learner profile of my ākonga, the majority that walk through my door are new learners of te reo Māori, lack the urgency and confidence to learn at a higher level, have less than 4 hours of te reo learning a week, and are from homes and environments where te reo Māori is not seen, heard, read or spoken (see poster below). The ākonga that enrol in my senior te reo Māori class are mainly those that are at risk and are often monitored by the school due to their truancy and lack of attendance. These are some of the harsh realities of working as a kaiako te reo Māori at kura auraki.

Who is speaking into this learning?

The New Zealand Curriculum guides kura auraki in the design and implementation of curricula that meet the diverse needs of their students. It recognises the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi and the bicultural foundations of Aotearoa, stating, “All students have the opportunity to acquire knowledge of te reo Māori me ōna tikanga” (Ministry of Education, 2015, p.9). It also acknowledges the principles of inclusive pedagogies, stating that “…it ensures that students’ identities, languages, abilities, and talents are recognised and affirmed and that their learning needs are addressed” (Ibid). However, like Morton et al (2021), I am also inclined to see the NZC, TAAM and NCEA as a curricula and syllabus that are accessible only to some and not all ākonga. NCEA fails to reflect the learning, strengths, and interests of some of our students. Te Aho Arataki Marau is irrelevant for some students, and therefore, I struggle, like many other kaiako, to see myself as a kaiako to all ākonga capable of learning te reo Māori. And like Paul and his team (Morton et al. 2021), I dare to propose a range of pathways that is not bound up in the vortex of the traditional NCEA formulae. Morton et al (2021, p.10), states:

“Successful education is not about the paper qualification accumulated by the time one leaves school, [but it] should be about students recognising their capability, believing dreams can be achieved, and having the skills and motivation to continue learning beyond school.”

Our primary role as kaiako Māori teaching te reo Māori in an English-medium setting, is to plant the kākāno of aroha and wawata to continue their language learning journey beyond school – that is where our biggest contribution to te reo Māori revitalisation lies. Instead, we continue to stifle the love and joy of learning for learning’s sake as we pursue an NCEA assessment and credit-driven exercise where there is only, according to one of my ākonga, “one answer to everything” (personal communication, October 11, 2022). It is no wonder my ākonga are giving up. In a report on the provision of te reo Māori in English-medium schools, entitled Whakanuia te reo kia ora (Murphy et al., 2019), the findings state that, “English-medium schools are making a critical contribution to the revitalisation of Māori language, particularly in terms of recognising and valuing te reo Māori as a key part of our national identity” (p.7). Even here our [English-medium school’s] contribution to te reo Māori revitalisation efforts is not known for its ability to successfully teach te reo Māori.

Te Tāmata Huaroa (2020) is a report that followed up on the evaluations made in Whakanuia te reo kia ora, and sought to investigate how schools are integrating and teaching te reo Māori in English-medium schools. The general attitude towards the importance of te reo Māori were found to be positive. However, this positivity was not seen to transfer into the student’s confidence to speak, read, and write, and therefore, as a whole, student achievement in te reo Māori remained within Level 1 of Te Aho Arataki Marau mō te Ako i Te Reo Māori (2009). These findings were not the least surprising to me. What is surprising to me, however, is how the 2020 report concluded that the “te reo Māori programmes often do not support progression towards higher curriculum levels over time” (p.23), after just identifying the poor teaching and learning conditions of our kaiako and ākonga. It is not the “te reo Māori programmes” that are not supporting our students, but it is a myriad of variables that are too long to list here.

More importantly, what is a possible solution that is within our [kaiako te reo Māori] power to change? It is to be able to design our own curriculum, pedagogy and assessment practices to meet the realistic and collaboratively co-constructured goals of the ākonga. A successful education, according to Morton et al (2021, p.8), is an inclusive one:

“Inclusive pedagogies encourage teachers to plan for all students from the outset by providing a range of choices in order to support learning for everyone.”

This is what it means to maintain a culture of learning, and a culture of belonging, an important factor for motivation.

My alternative suggestion includes both a zero credit pathway and an accredited one (see last question). When conversing with my in-school mentor, he was quite critical of my suggestion. His view was that having a zero credit pathway will add more pressure on other teachers to meet the student’s credit requirements (Moyes, personal communication, May 19, 2022). It is a valid position. However, my question is, what about the overwhelming pressures and workload placed on kaiako Māori to get their ākonga up to standard? After all, learning to be conversational, let alone gain credits, in te reo Māori as a new learner is no easy undertaking, especially in a school that does not provide the necessary support and conditions for effective acquisition of te reo Māori. With a collaboratively co-constructed plan with their subject kaiako, ākonga can factor in where and how they will accumulate their credits.

Why does this matter as a teacher for social justice?

All of the reports are continuing to paint a bleak image of English-medium schools where kaiako Māori continue to be underserved, and as a result, ākonga enrolled in their classes continue to underperform. As a kaiako whose role is inherently political (Lee, 2008), I have a central role to champion an inclusive education, which is a political activity of striving for a school community of equity and diversity. In order to improve our (kaiako Māori) situation in a Euro-centric environment, we cannot be complacent or comfortable, as Paraone Gloyne advises, “Kia kaua e noho hāneanea! Ko te mea nui ko te koke, ko te koke, ko te koke” (personal communication, October 4, 2022).

How will this look in my practice moving forward?

After a number of wānanga with my ākonga, we arrived at three to four possible pathways for learning te reo Māori.

- A unit standard pathway for ākonga who only wish to learn about mātauranga Māori without the added pressure of having to listen, write, read and speak te reo Māori.

- A beginner te reo course where the kaiako teaches all the foundational stuff and decides at the end what to assess their ākonga. Assessments design is based on where ākonga are currently in their te reo Māori journey and not where they should be according to TAAM.

- Te Aho Arataki Marau and NCEA Achievement Standards should be an optional or suggested pathway for ākonga who have had prior immersion learning (i.e. KKM, wharekura), or who have a strong desire to pursue a higher level of te reo Māori learning.

- A pathway that interweaves two or all of the above pathways. An ākonga, for instance, can start with option number 1, progress to option number 2, and move on to option number 3, where they may feel ready and confident to complete an achievement standard of their choosing.

Te Aho Arataki Marau should be optional to follow in kura auraki. It should only provide guidelines rather than a checklist for kaiako to tick off. Kaiako and ākonga may even perhaps want to add two or all pathways into a ākonga learning plan. The point is, kaiako Māori, in collaboration with ākonga, should be given the creative license and flexibility as to how ākonga programmes and assessments are designed and implemented. After all, all our communities are diverse, and then there are even more diversities within those diversities. We have a myriad of learners and kaiako in our school and community spaces, so why do we teach to one blanket syllabus such as Te Aho Arataki Marau?

There are many benefits to following this model here at my kura. Yes, this may create more work for me, and it may also mean my senior ākonga will need to rely on their other subjects for NCEA credits. However, I believe creating multiple pathways for te reo is student-centred as it is tailored to the desires and aspirations of our ākonga. It also eliminates the issue of continuously having to fill gaps for ākonga who have little to no te reo Māori. These avenues will lesson the learner burden and pressure that is often faced by ākonga as new learners of te reo Māori. These pathways would follow an assessment for learning approach as opposed to learning for assessment.

NGĀ TOHUTORO

Education Review Office – Te Tari Arotake Mātauranga. (June 18, 2020). Te Tāmata Huaroa: Te Reo Māori in English-medium Schooling [report]. Education Review Office.

Lee, J. (2008). Ako: Pūrākau of Māori teachers’ work in secondary schools. [Thesis]. The University of Auckland.

Ministry of Education. (2015). The New Zealand Curriculum: for English-medium teaching and learning in years 1-13. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (2009). Te Aho Arataki Marau mō te Ako i Te Reo Māori – Kura Auraki: Curriculum Guidelines for Teaching and Learning Te Reo Māori in English-medium Schools: Years 1-13. Learning Limited Media.

Morton, M., McIlroy, A. M., Macarthur, J., & Olsen, P. (2021). Disability studies in and for inclusive teacher education in Aotearoa New Zealand. International Journal of Inclusive Education, pp.1-16.

Murphy, H., Reid, D., Patrick, A., Gray, A., & Bradnam, L. (2019). Whakanui te reo kia ora: evaluation of te reo Māori in English-medium compulsory education [report prepared for Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori]. Haemata Ltd.

| STANDARD | ELABORATION |

| Standard 1: Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnerships Demonstrate commitment to tangata whenuatanga and Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership in Aotearoa New Zealand. | • Understand and recognise the unique status of tangata whenua in Aotearoa New Zealand. • Understand and acknowledge the histories, heritages, languages and cultures of partners to Te Tiriti o Waitangi. • Practise and develop the use of te reo and tikanga Māori. |

| Standard 3: Professional relationships Establish and maintain professional relationships and behaviours focused on the learning and wellbeing of each learner. | • Engage in reciprocal, collaborative learning-focused relationships with: – learners, families and whānau – teaching colleagues, support staff and other professionals – agencies, groups and individuals in the community. • Actively contribute, and work collegially, in the pursuit of improving my own and organisational practice, showing leadership, particularly in areas of responsibility. • Communicate clear and accurate assessment for learning and achievement information. |

| Standard 4: Learning-focused culture Develop a culture that is focused on learning, and is characterised by respect, inclusion, empathy, collaboration and safety. | • Develop learning-focused relationships with learners, enabling them to be active participants in the process of learning, sharing ownership and responsibility for learning. • Foster trust, respect and cooperation with and among learners so that they experience an environment in which it is safe to take risks. • Demonstrate high expectations for the learning outcomes of all learners, including for those learners with disabilities or learning support needs. • Manage the learning setting to ensure access to learning for all and to maximise learners’ physical, social, cultural and emotional safety. • Create an environment where learners can be confident in their identities, languages, cultures and abilities. • Develop an environment where the diversity and uniqueness of all learners are accepted and valued. • Meet relevant regulatory, statutory and professional requirements. |

| Standard 5: Design for learning Design learning based on curriculum and pedagogical knowledge, assessment information and an understanding of each learner’s strengths, interests, needs, identities, languages and cultures. | • Select teaching approaches, resources, and learning and assessment activities based on a thorough knowledge of curriculum content, pedagogy, progressions in learning and the learners. • Gather, analyse and use appropriate assessment information, identifying progress and needs of learners to design clear next steps in learning and to identify additional supports or adaptations that may be required. • Design and plan culturally responsive, evidence-based approaches that reflect the local community and Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership in New Zealand. • Harness the rich capital that learners bring by providing culturally responsive and engaging contexts for learners. • Design learning that is informed by national policies and priorities. |

| Standard 6: Teaching Teach and respond to learners in a knowledgeable and adaptive way to progress their learning at an appropriate depth and pace. | • Teach in ways that ensure all learners are making sufficient progress, and monitor the extent and pace of learning, focusing on equity and excellence for all. • Specifically support the educational aspirations for Māori learners, taking shared responsibility for these learners to achieve educational success as Māori. • Use an increasing repertoire of teaching strategies, approaches, learning activities, technologies and assessment for learning strategies and modify these in response to the needs of individuals and groups of learners. • Provide opportunities and support for learners to engage with, practise and apply learning to different contexts and make connections with prior learning. • Teach in ways that enable learners to learn from one another, to collaborate, to self-regulate and to develop agency over their learning. • Ensure learners receive ongoing feedback and assessment information and support them to use this information to guide further learning. |

| COMPETENCY | A STUDENT TEACHER |

| Wānanga: Communication, problem solver, innovation Participates with learners and communities in robust dialogue for the benefit of Māori learners’ achievement. | • Demonstrates an open mind to explore differing views and reflect on own beliefs and values. • Shows an appreciation that views which differ from their own may have validity. |

| Whanaungatanga: Relationships (students, school-wide, community) with high expectations. Actively engages n respectful working relationships with Māori learners, parents and whānau, hapū, iwi and the Māori community. | • Can describe from their own experience how identity, language and culture impact on relationships. |

| Manaakitanga: Values – integrity, trust, sincerity, equity. Demonstrates integrity, sincerity and respect towards Māori beliefs, language and culture. | • Values cultural difference. • Demonstrates an understanding of core Māori values such as: manaakitanga, mana whenua, rangatiratanga. • Shows respect for Māori cultural perspectives and sees the value of Māori culture for New Zealand society. • Is prepared to be challenged, and contribute to discussions about beliefs, attitudes and values. • Has knowledge of the Treaty of Waitangi and its implications for New Zealand society |

| Tangata Whenuatanga: Place-based, socio-cultural awareness and knowledge. Arms Māori learners as Māori – provides contexts for learning where the identity, language and culture (cultural locatedness) of Māori learners and their whānau is armed. | • Knows about where they are from and how that informs and impacts on their own culture, values and beliefs. |

| Ako: Practice in the classroom and beyond. Takes responsibility for their own learning and that of Māori learners. | • Recognises the need to raise Māori learner academic achievement levels. • Is willing to learn about the importance of identity, language and culture (cultural locatedness) for themselves and others. • Can explain their understanding of lifelong learning and what it means for them. • Positions themselves as a learner. |

| TURU | ELABORATION |

| Turu 1: Identities, languages and cultures Demonstrate awareness of the diverse and ethnic-specific identities, languages and cultures of Pacific learners. | 1.1 Understands his or her own identity and culture, and how this influences the way they think and behave. 1.3 Is aware of the diverse ethnic-specific differences between Pacific groups and commits to being responsive to this diversity. |

| Turu 2: Collaborative and respectful relationships and professional behaviour Establishes and maintains collaborative and respectful relationships and professional behaviours that enhance learning and wellbeing for Pacific learners. | 2.2 Understands that there are different ways to engage and collaborate successfully with Pacific learners, parents, families and communities. 2.3 Is aware of the importance of respect, collaboration and reciprocity in building strong relationships with Pacific learners, their parents, families and communities. |

| Turu 3: Effective Pacific pedagogies Implements pedagogical approaches that are effective for Pacific learners. | 3.1 Recognises that all learners including Pacific are motivated to engage, learn and achieve. |