KARL WIXON

Ako Panuku Hui ā-Tau 2021

Ki te taha o tōku hākoro – Ko Takitimu rāua ko Uruao ōku waka. Ko Motupōhue te mauka. Ko Awarua te awa. Ko Te Ara-a-Kewa te moana. Ko Te Rau Aroha tōku marae. Ko Ngāi Tahu, ko Kāti Māmoe, ko Waitaha anō hoki ōku iwi. He uri au nō Rongomaiwhenua, te Imi Moriori ki Rēkohu. Ki te taha o tōku hākui – ko Tainui te waka. Ko Tokomaru te maunga. Ko Wairau te awa. Ko Wairau te marae. Ko Ngāti Toa Rangatira te iwi.

Karl Wixon – Director of ARAHIA – specialises in envisioning, co-designing and achieving positive futures through leadership, strategy, change, growth and innovation. Karl brings a marriage of commercial, creative, and cultural acumen to all he does and is frequently called on as a skilled Māori co-design facilitator to weave together complex collaborations spanning cultures, sectors, entities and interests to develop vision, direction, and innovative solutions. A husband and father of three teens, Karl has been actively involved with schools, on Boards of Trustees as a Chair, as a hockey umpire, school representative coach, and as a mentor on the Young Enterprise Scheme and Tahu Scholarship founded at Woodford House by the Drury Whānau.

Below are some of the themes and kōrero captured from Karl Wixon’s presentation.

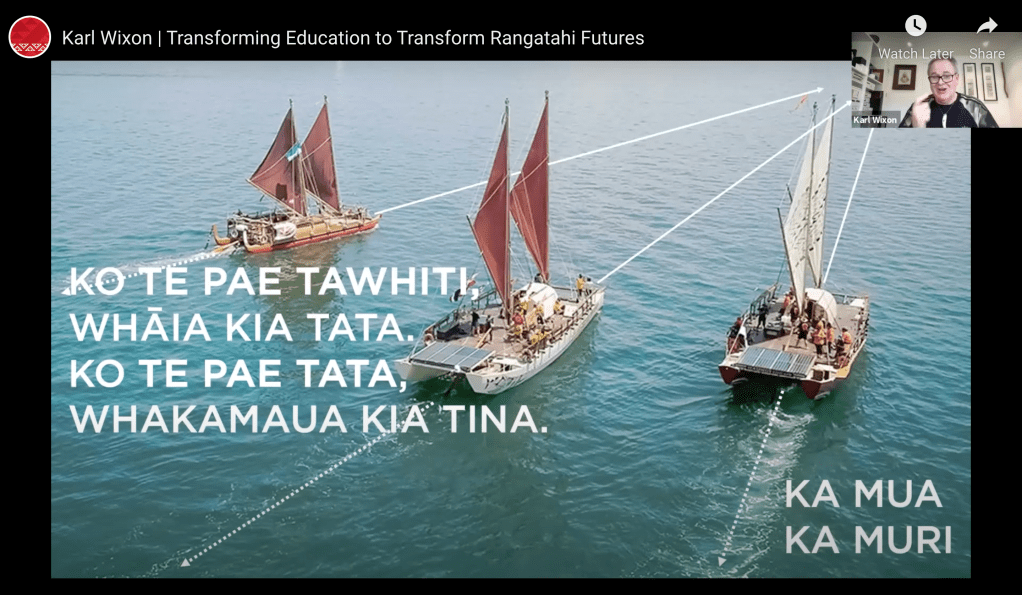

Manifesting Our Destinations – Te Pae Tawhiti

How are we designing the future of our rangatahi (youth)? How are we making the shift happen? We help our rangatahi manifest in their mind the destination they wish to pursue and fix their points on.

The blueprint of this is in our whakataukī: Ko te pae tawhiti whāia kia tata, ko te pae tata whakamaua kia tina.

If you were to ready your voyaging waka on the shore to depart to an unknown destination, beyond the visible horizon, the tohunga (priest) would stand with you until you could manifest in your mind that destination. You did not leave that beach until that destination was manifested in your mind, and then you were able to set your sights on the near horizon (te pae tata), to trig fix your point and say that that’s the trajectory, and that’s where we are aiming and that’s how we will get there.

The phenomena of this one, when we’re talking in the Pasifika voyager context, as you journey to that horizon it keeps changing.

As you journey [on your waka hourua] your journey is disrupted, the winds change, the ocean currents shift, it’s a dynamic movement of a perpetual horizon, of a continuous voyage without end.

Karl Wixon, 2021

That to me is a really important way about how we frame futures. It is the relentless pursuit of the envisioned destination with agility and adaptation in between. That whakataukī asks us to do that…

…that before we leave the beach we set our points on that destination beyond the visible horizon [pae tawhiti] and then we backcast to set our point on the visible horizon [pae tata] that will get us there and we hold dear to that and pursue it.

We do that by acknowledging that what’s in front of us [te pae tawhiti] will be guided by what’s behind us [te pae tata] – ka mua, ka muri. The blueprint for our future visions are in our kōrero (stories), pūrākau (legends) and whakataukī such as this one.

My Other Education/School

“Never let your education get in the way of your learning.”

Mark Twain

For Wixon the learning was happening not just in the classroom, but also in the taiao (environment). His other school was being held at the motu tītī (mutton bird island) named Poutama, off the South-East coast of Rakiura (Stewart Island). Two months every year they were there during the tītī harvest season. This mahinga tītī (mutton bird harvest) was the vocation that he was raised in and it’s an inter-generational whānau (family) enterprise. Not only was it an inter-generational whānau enterprise, it was their whare wānanga (place of higher learning). This is where Wixon and his whānau had their ‘other education.’

They would go as three generations on an Island together. The grandparents teach the mokopuna (grandchildren). The older generations take the responsibility of passing on this knowledge and customary practices onto the younger generation. This is unbroken intergenerational transmission of customary knowledge. They were the kaitiaki or resource custodians of those resources on that Island. He felt disheartened when he would see kaitiakitanga, manakitanga, whanaungatanga on the walls of corporations. For him they are not merely optional aspirations and ideals to be hung on walls. Being a kaitiaki, for him, is not a choice, but it is a necessity.

“Because it is your livelihood and your wellbeing is directly interdependent of the environment you are occupying and the resources for which you are reliant on for your wellbeing, you have that duty of care and you have a sense of consequence because you see the direct consequences of your actions. So these are not fluffy ideas, these are realities. They are pragmatic practices.”

Karl Wixon, 2021

Wixon is right because our ancestors were pragmatic people who have developed their own self-sustaining resource management system they had fine-tuned over the hundreds of years of occupying these whenua and being dependent on their taiao for their well-being and sustenance (Kawharu, 2002).

While he was getting an education in school, his learning and birding practices on Poutama with this whānau is what has informed who he is. “Knowing that 500+ years of trade and tradition is in our DNA” (Wixon, personal communication, Tuesday 5 October 2021). We have always been global citizens. We have also always been innovators and problem solvers. When defining and describing our culture, Tā Tipene O’Regan says that

“We come from a culture of dynamic adaptation and rapid adoption.”

Wixon, 2021

What is the Māori Story?

According to Wixon: “We are people of the land and sea, living the legacy of our ancestry every day, through our bold adventurous spirit, our love and care for people, and our deep connection with place, āke tonu atu.”

In terms of the aspirations and drive that the Māori story gives, here are further words from Tā Tipene O’regan:

“We must develop a new generation of leaders, people we can trust with the assets that our generation has begun to recover...It’s our mokopuna’s assets we’re talking about here - nothing short of the world’s best is good enough for them. We must embrace excellence and pursue it obsessively.” For Tā O’Regan, “Only excellence will achieve the rangatiratanga of which we dream.”

Here Tā O’Regan talks about the new generation of leaders we need to entrust with our assets that we’ve had to fight to get back. These are lofty aspirations. So how do we embed these aspirations into our rangatahi?

The Need of a Base Camp

Whāia te iti kahuranga, ki te tūohu koe me he maunga teitei – follow that which you treasure most, and should you bow, let yourself be like the highest mountain. Wixon adds to this by saying that if we are to pursue those lofty heights we must get into uncharted territory.

“We must take big endeavours and big risks. However, we need to do it in the comfort and safety of a base camp.”

Wixon, 2021

Tūrangawaewae

What is it that grounds you, that stabilises you, that you can return to that provides confidence, safety, security and stability? Our rangatahi need the same thing. If we want them to innovate, to aspire to the loftiest heights we have to give them their base camp. For a lot of us that is our tūrangawaewae. That base camp is the one place we can stand and where we have the authority to speak. We are the knowledge carriers. We make the decisions. We can stand here with confidence, where others are not allowed. That place, our place of standing, is our tūrangawaewae” (Karl Wixon, personal communication, Tuesday 5 October 2021). So the task that Karl Wixon took on with his children was to ensure they continue to have a base camp.

Aptitude, Attitude, and Altitude

The aspirational part…what is it that we need to do? Aptitude, attitude and altitude. We need to identify and foster the talents in our kids. Not make them fit the mould, but make the mould fit them. Attitude is everything, such as work-ethic, self-belief, the commitment to, the desire. Altitude…how lofty is it? Are we really elevating these aspirations? What are we doing to lift that altitude? Normalising conversations about things like, “when you get your degree…,” “when you start your business…,” “when you invent….” These are the [high] expectations you have for your tamariki and become normalised in household conversation. His own children are a living and breathing byproduct of these expectations and household conversations.

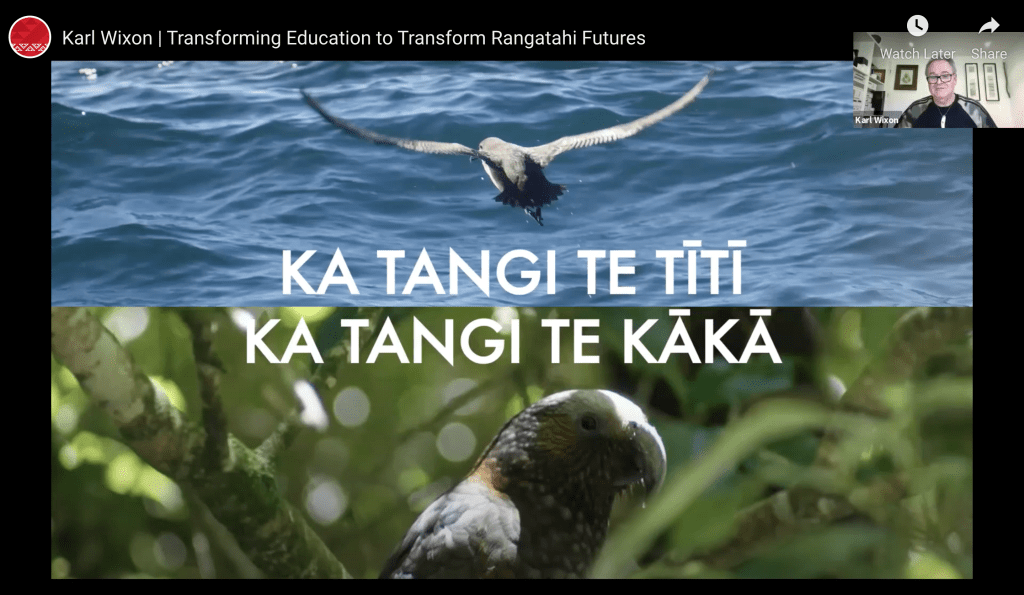

Local and Global Intel

This tauparapara draws on the global and local intel and insight that these two birds bring to bear. Just as te pae tawhiti and te pae tata also draw on near and far, so do these two birds bring insight and intel from a global (tītī) and local (kākā) perspective. These cultural blueprints give us a cultural sensibility and way of looking at the world.

Wixon advocates for us to be both the manu (bird) that eats the berries from the forest, and the manu that eats the berry of knowledge – ko te manu e kai ana i te miro, nōnā te ngahere; ko te manu e kai ana i te mātauranga, nōnā te ao. Perhaps this whakataukī was our ancestors telling us to continue to feast on the berries of our kāinga (home), but to also venture out into unchartered territory and seek other fruits, but to always come back to the kāinga. Dr. Irwin also supports this view in her empowering words telling us to go ahead and enjoy the fruits of both worlds so that we may be adept border-crossers.

Marian Wright Edelman sums it up nicely when she stated:

“You can’t be what you can’t see.”

Marian Edelman

If our rangatahi have got no exposure, no vision, no self-belief, no end opportunity in sight it is very very hard to get there. It’s very hard to wake up with a sense of purpose and get out of bed in the morning and get on with a sense of drive. For Wixon the above are actionable steps that we as kaiako and public servants can start doing today. Wixon urges us “to create connections and take action today!” (LINK THIS TO MY EXPERIENCE IN SCHOOL AND THE KŌRERO THAT RENEE SAYS, THAT IF WE DON’T DEAL WITH ALL OF THIS, THEN THERE IS NO LEARNING)

How do we as kaiako create a line of sight to the future and to opportunity for our rangatahi? How do we take action today that joins the dots for them? Wixon answers: “It’s out there and not here.”

Instruments of Education Reform

Education and Training Act 2020

This Act states that it is incumbent upon the Crown to establish and regulate an education system that –

(d) honours Te Tiriti o Waitangi and supports Māori-Crown relationships.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi

Article 1 – Kāwanatanga

Crown is responsible for establishing and regulating the education system, and in doing so honouring Articles 2 & 3.

- Legislation

- Regulations

- Policy

- Structure

- Strategy

- Qualifications

- Credentials

The last two are what we as Māori, iwi, and hapū need to get a seat at the table of decision-making for our people.

Article 2 – Rangatiratanga

Māori have full control over taonga Māori, including te reo, tikanga me mātauranga Māori.

The following are instruments that can liberate or dismantle these pursuits:

- Partnerships with local iwi

- Understanding and responding to iwi needs

- Sharing power and resources

Article 3 – Mana Ōrite

Ensure Māori have equal rights, access, opportunities and outcomes as non-Māori (…rite tahi…)

The following are instruments that can liberate or dismantle these pursuits:

- Equity

- Attraction, recruitment and retention

- Targeted scholarships

- Tauira needs

- Responsive, etc.

The biggest wero, however, is to liberate the school/classroom space for Māori to be Māori.

Almost 200 years on and we are still trying to undo the damage that was done two centuries ago.

Mātauranga Māori

- Article 2: Mātauranga Māori is recognised as a taonga.

- Rangatiratanga means iwi and hapū led and controlled.

WAI262 Report

- ‘Ko Aotearoa tēnei’

What ‘doing good’ looks like:

- Iwi, hapū, Māori led and controlled.

- Use of mātanga Māori (Māori experts) to develop, deliver, assess, etc.

- Tribal context recognised e.g. Matariki knowledge varies by iwi.

What ‘doing bad’ looks like:

- No Māori engagement or partnerships to assure cultural authenticity, credibility or defensibility of Mātauranga Māori.

“Cultural assurance is your cultural insurance.”

Wixon, Oct 5, 2021

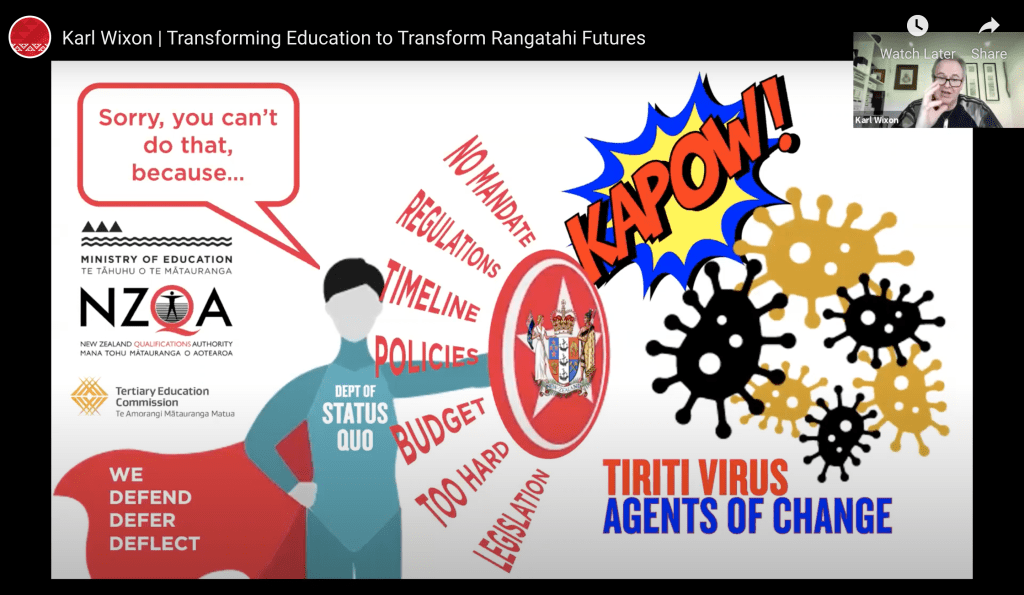

The ‘Tiriti Virus’

Wixon also talks about the inertia of the present education system. (LINKS TO MY THOUGHT about schools not being relevant: we need a bigger change). There is a huge amount of resistance and inertia of the status quo towards transformative change – he calls it the Tiriti Virus (see image below).

When we are pushing forward our visions, our aspirations and expectations the response is quite often a word starting with ‘def’ – defend (in defence of the status quo), defer (“great idea maybe we can do that in the next review in 3 years”), deflect (“that’s not my responsibility that’s another department”).

They (the status quo defenders) hide behind a shield of regulations, timelines, policies, budget, too hard basket, legislation, and there’s no mandate. There are a myriad of reasons or excuses this immune system puts up its barriers to resist change and to resist what Wixon calls the “Tiriti Virus.” The rhetoric is not being aligned with the behaviour. That which is being represented in legislation and espoused in the high-level rhetoric is not matched in action. The action is quite contrary in many cases.

It comes back to the blueprint of te pae tawhiti and te pae tata. The power of being able to manifest the destination in the mind before we leave the beach. It is incumbent upon us to try and build that clarity of what it is we want and what our rangatahi want and for them to build their own clarity to make it explicit enough and tangible enough that we can begin that journey.

A lot of our rangatahi do not have that tūrangawaewae, or that base camp. What are the things that will build that? If they don’t know their whakapapa, if they don’t know their whenua, if they’re not connected to their whānau beyond a couple of people or even don’t know who their grandparents or their great grandparents are, how do we provide that proxy of tūrangawaewae? That sense of place, sense of belonging, sense of identity. It’s a challenge, I know, but it’s through the kōrero and through the exploration and through the questioning that we start to get that sense. If we can build that base camp, we are free to explore, but also coming back and acknowledging our own knowledge, our own ontology, that sits behind our pedagogy (the manu eating the berry of knowledge, must return to their forest).

Conceptual Frameworks

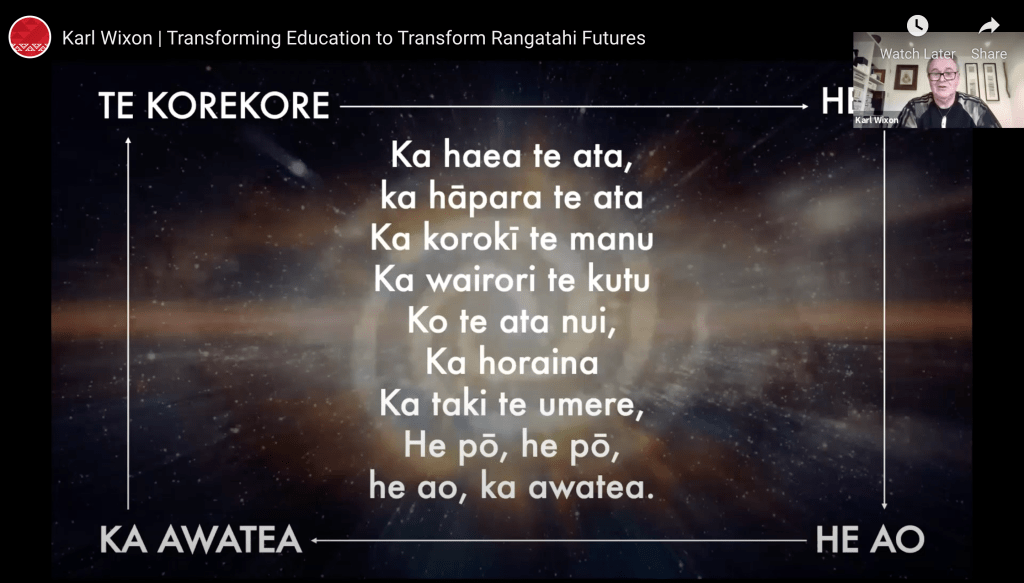

We have our own indigenous innovation frameworks (see image below):

The above is one of the Ngai Tahu creation narratives. These frameworks are Māori innovation cycles. This is the creative process – from conception to birth, from absence of mind to consciousness, from the nothingness to light, etc, etc. We have our creation stories and narratives; we just need to apply them in a modern context.

“I am a firm believer that all the tools we need are all there in our culture.”

Wixon, 5 Oct, 2021

Deeply embedded in us are our cultural sensibilities and place-based sensibilities.

Karakia

Kei runga ko Ranginui

Kei raro ko Papatūānuku

Kei mua ko te moana

Kei muri ko te ngahere

Kei tēnei taha ko ngā awaawa, ko te puna wai

Kei tērā taha ko ngā wāhi mahinga kai

Kei konei ko te kāinga, ko ngā oranga katoa

E ko koia, e ara e!

It is a beautiful karakia (prayer) about grounding and placing, and positioning ourselves between Ranginui (Sky Father) and Papatūānuku (Earth Mother) within our taiao (environment). This is the base camp that Wixon speaks of, it is a positioning system that places the person within a culturally, spiritually, environmentally, economically, and socially secure locality. For Wixon, it places him in front of the ngahere (forest), which is the source of our sustenance, but he faces towards the moana (sea), to the perpetual voyaging horizon where he projects his imagination into the distance – ko te pae tawhiti, ko te pae tata, ka tangi te tītī, ka tangi te kākā, kei muri ko te ngahere, kei mua ko te moana, it all links up.

I think back to Peter O’Connor and his kōrero about imagination and creativity and the ability to just imagine. Transformative change cannot happen without being able to visualise or imagine what it is we want, thus giving credence to the saying, “we cannot be what we cannot see.”

Q & A

How do we create a base camp for our tauira who do not have one?

Bringing in the whānau is a prerequisite to building a base camp because what goes on in our schools is disconnected most times from what is going on at home. These tamariki do not come on their own, they have whānau they belong to. How do we build confidence? How do we build security? How do we build connections? We need to create a safety-net, so that our tauira feel that it is okay to fall and that it is okay to trip because we got you.

How do we foster aptitude, attitude and altitude?

We foster it by talking it up. We foster it by normalising the kōrero that is aspirational. We foster it by normalising high expectations of them. Not to push them down and be critical but by normalising the language of strength-based, confidence-based aspirational lift.

“The most powerful thing that they (our tamariki) can have is self-belief…If you have that self-belief it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Wixon, 5 Oct, 2021

We gotta fuel that, we gotta create that self-belief. If we build confidence it becomes a snow-ball effect. If we get success it snowballs. Success breeds success. Get the snowball going. Then they are unstoppable. We have to be the catalyst of their confidence, which then becomes a snow-ball effect.

Wixon admits that “it is easier said than done, but every kōrero matters.” There is power in our words and what we say. In his presentation, Leon Te Heketū Blake states, “he mana tō te kupu.” The words you write or speak to others can leave a huge impact and create a lasting-memory – either good or bad – so it’s super important to choose them wisely. That is applicable in the classroom. What we say as teachers have a huge impact on our ākonga. Words can echo long after they are spoken. He urges us to “light the fire” or “fuel their interests and talents.” It doesn’t take a lot to raise hope and aspiration. We must recognise an interest or a talent and connect it to the matrix of opportunity and aspiration.

How do we foster that sense of belonging and tūrangawaewae using that karakia where they are grounded in the taiao?

We must take them outside and into the taiao. To learn about where our designs and innovations came from, we must go into our taiao. Te taiao and te tai moana are our source, they are our puna mātauranga. We need to reconnect our tauira with that puna. We cannot reconnect them with that mātauranga when we do not reconnect with the puna.

Children who have no connection to their tūrangawaewae or their whānau, what is an alternative base camp we can create for them?

Anyone who has aroha for and confidence in these kids. Talking them up. Complimenting them on their talents. A confidence a child experiences on the field (as Wixon had demonstrated) can transfer that into the classroom. Their base camp can come from different places. The tūrangawaewae can be that confidence in self, it can be an inner-space where our kids can draw their power, their sense of self, sense of confidence, sense of belief and belonging. As long as there is somebody who has their back, who tells them they are great and that they are destined for great things. It is how we are interacting with our kids and what we are telling them what is good or bad and squashing some attributes and elevating others.

Reference

Wixon, K. (2021, October 5). Transforming the futures of rangatahi by transforming education. [Keynote address]. Ako Panuku Hui ā-Tau, New Zealand. https://akopanuku.tki.org.nz/information/hui-a-tau-2021-ondemand/