Enabling Pasifika Literacy Success

Keynote Speakers: Dr. Rae Si’ilata & Kyla Hansell

We all sat on stackable school chairs which had been placed in rows all down Glen Taylor’s school hall. The chairs were facing the keynote speaker’s podium at which stood the astute and charismatic Dr. Rae Si’ilata (Fijian, Ngāti Raukawa/Tūhourangi) and her protégé Kyla Hansell (Ngāpuhi, Samoan, German).

When Dr. Si’ilata addressed the assembly, she spoke with such eloquence and clarity that she had us all in the palm of her hands. There was no ums and aahs in her presentation. This wahine knew her stuff, and she knew it well.

Her ‘big idea’ question: What is effective practice when it comes to reading, and what is effective practice for our Pasifika communities? Of particular salience for Dr. Si’ilata are effective bilingual and biliteracy reading strategies for Pasifika learners for whom English is their second/third language. How can teachers help Pasifika learners succeed in English, while also maintaining their native language? Below are some of the key themes and learnings I took away from her kōrero.

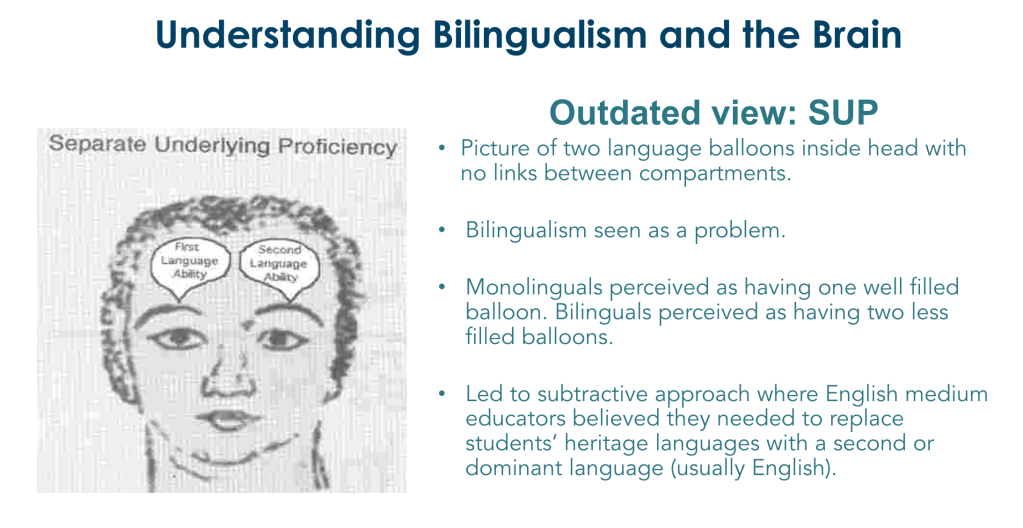

It is an outdated view to see the brain as separate. For example, the colonising powers believed and taught to peoples of the Pacific and Aotearoa that to learn English, the Pacific and Māori people must no longer speak their heritage language at school. Wrong advice!

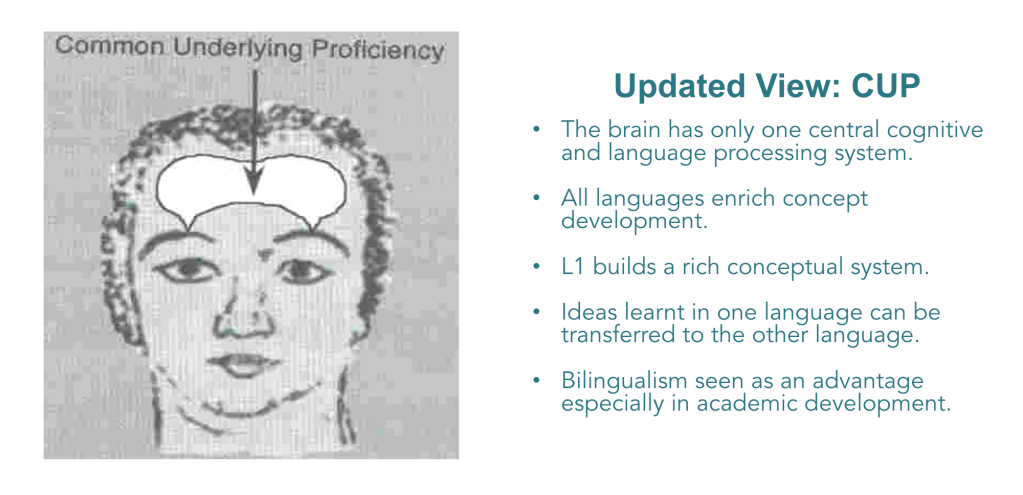

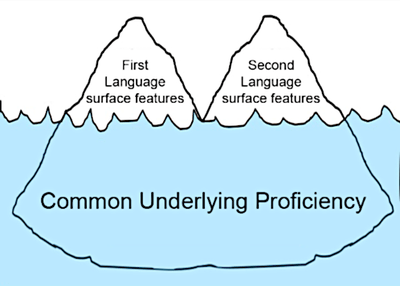

We now recognise that there is interdependence across the language resources. Leaner’s can transfer their ideas from one language to another via the brain’s central cognitive and language processing system, also known as Common Underlying Proficiency (CUP). Irrespective of the language in which a person is operating, there is one integrated source of thought (Baker & Write, 2017). Therefore, limiting the thinking to prior knowledge encoded in English learning only is to only tap into a very small portion of the learner’s prior knowledge.

“Generally what a bilingual will do, they will receive input in one language, input in English, and if their first language is stronger than English they will make sense of what they’re hearing, they will translate into their stronger language, make sense of it, think of their response and then output, translate back or transfer back and output in English. That’s how a bilingual brain works, you think of any time when you’ve learned another language, you make meaning in your stronger language, but not just your language, you make meaning through your cultural ways of being and through your worldview”

Si’ilata & Hansell, 2021

Jim Cummins (1981) uses the iceberg metaphor to illustrate how the bilingual brain operates. However, there are not too many icebergs in Aotearoa New Zealand. Dr. Sophie Tauwehe Tamati uses the kahikatea metaphor to visualise the bilingual brain. Using my own cultural capital, I was able to visualise a root system that is intertwined and interconnected, while the trees above appear to be separate. Tamati uses the kahikatea metaphor to illustrate the brain as having organic linguistic fluidity (2016, p.10).

So we need to think about this in our classrooms from new entrants up to Year 13. Are we privileging the language and cultural resources that rangatahi are bringing with them to kura so they can make connections to the curriculum that we promote in our akomanga? So, irrespective of the language a person is operating, there’s one integrated source of thought. Learners can develop information processing skills in two languages as well as one. Speaking, listening, reading, or writing in the heritage language and English helps develop the learner’s whole cognitive system. However, forcing learners to operate in the classroom only in the register of school English will negatively impact their curriculum learning.

Integration of Communication Modes

Dr. Si’ilata emphasises the importance of integrating all six communicative modes. Reading should not be taught in isolation to writing, just as speaking should not be taught separate from listening. It is particularly important to integrate all communicative modes for emergent bilingual learners.

Privilege the Native Speaker

Dr. Si’ilata’s expertise and passion is in the areas of bilingualism and biliteracy, particularly in the Pacific education and TESOL (Teaching English in Schools to Speakers of Other Languages) spaces. Dr. Si’ilata suggests that kaiako create additive educational spaces where kaiako add English to their learner’s language repertoire rather than replace their heritage language. Dr. Rae Si’ilata states:

“we need to give our tamariki the keys to the language of the culture of power, which is what Lisa Delpit said…but that’s not enough on its own. We need to give them those keys to the language of the culture of power but we need also to create an additive educational context where we are adding the language of power to their language and cultural resources that they bring with them”

Si’ilata & Hansell, 2021

Although being culturally responsive is important, for Dr. Si’ilata it is not enough:

“I believe, we as educators have an educational responsibility for language revitalisation for language maintenance for you know, to be culturally responsive is not enough. It’s not enough. We need to be linguistically and culturally sustaining and revitalising in all of the mahi that we do across the curriculum”

Ibid

Dr. Si’ilata asks us to “privilege the native speakers” in our classrooms. In other words, we need to recognise the language and cultural resources coming into our classrooms and create spaces for the expertise that’s nested within our classes to be privileged.

Heritage Literacy Practices

It is important to retain and integrate heritage literacy practices within the classroom. By doing so, kaiako privileges and values the learner’s worldview as our worldview informs our literacy practices. From a Māori perspective, our literacy practices are informed by a worldview that was generationally transmitted orally through waiata, haka, whaikōrero, and pūrākau, to name a few.

When Dr. Si’ilata spoke about her Māori father, she lovingly stated that despite his having been diagnosed with dementia, waiata and haka were deeply embedded in her father’s wairua (spirit). Many of these privileged literacy practices in our whānau spaces are not privileged in our school spaces. Many of our Māori and Pacific peoples have literacy practices that, like Si’ilata’s father, are deeply embedded in their hearts and spirits.

He kura pae nā Māhina e kore e whakahoki atu ki a koe The red ornament found by Māhina will not be returned to you.

This whakatauākī referred to when the Te Arawa waka neared the end of its migratory voyage. Tauninihi saw with amazement the plentiful blooms of the pōhutukawa tree growing on the shore of Whangaparāoa. He thought they were the same as the red feather adornment he had brought from Hawaiki, so he cast his aside but then discovered that the red plumes were flowers that quickly wilted and discoloured in the sun. Māhina would find the discarded adornment and refuse to return it, quoting the above whakatauākī (Si’ilata & Hansell, 2021).

Dr. si’ilata and Kyla Hansell use the above whakatauākī to urge whānau, learners and kaiako who come through English medium education with a rich repertoire of cultural knowledge and heritage literacy practices, to not be too hasty to cast aside our cultural treasures.

Dr. Si’ilata also invites us kaiako to ask ourselves, who holds the position of power in the classroom? Are we creating a subtractive context, where we are supporting our tamariki to successfully acquire English, while at the same time, we are removing the heritage language and cultural resource? Or are we creating power-sharing additive spaces where we are supporting learners to hold on to their treasured heritage practices and language while at the same time adding English to their cultural and linguistic repertoire?

Learning from Māori and Pacific Medium Education

The only education systems that have goals around bilingualism and biliteracy are Māori medium and Pacific medium education. Māori medium education is producing the best outcomes for Māori learners. There is a lot we can learn from Māori medium education. What are Kōhanga Reo, Kura Kaupapa Māori and Wharekura doing that is not being done in English medium education? Whose knowledge is valued in English medium education? Who holds the power in the English medium education classroom? These are all questions that Dr. Si’ilata asks us to ponder and reflect on.

Translanguaging Pedagogy: An Act of Social Justice

It is through translanguaging that learners are able to make meaning using their stronger language and cultural world view. Translanguaging is when a student reads an English text, and then processes it cognitively and produces it verbally in their stronger language. Enacting translanguaging in education calls for teachers to open up translanguaging spaces. This is an agentic space where power is shared with the learner. Making room for translanguaging is, according to Garcia & Kleifgen (2019):

“…disrupting established monolingual and monoglossic language and literacy understandings to make room for translanguaging, a teacher engages in acts of social justice, providing marginalized multilingual learners opportunities to act as literate multilingual learners, able to use their entire semiotic repertoire”

Garcia & Kleifgen, 2019, p.7

As teachers, we can affect the most positive change in the reading literacy of our learners by first being open minded and allowing the culture of the learner to enter the classroom. However, according to McKenzie & Singleton (2009):

“The culture of the child cannot enter the classroom until it has first entered the consciousness of the teacher“

McKenzie & Singleton, 2009, p.5

Prior Knowledge and Mirror Texts

Nowhere is the role of prior knowledge more important than in second language educational contexts. Learners who can access their prior knowledge through the language and culture most familiar to them can call on a rich array of schemata. One way kaiako can allow learner’s to unlock their prior knowledge is through using mirror texts. Kyla Hansell describes mirror texts as texts or materials that reflect our learner’s faces and experiences. The antonym of mirror texts are window texts. The latter offer windows into world-views that are not familiar to the emergent learner. Readers cannot make sense of their text without first connecting with who they are and their experiences. Many of the Pasifika dual language books (Fig. 1) connect with the Pasifika learner’s lived experiences and lives.

The following Hawaiian whakataukī (proverb) is used to stress Dr. Si’ilata’s view that the educational system is only one of many places where knowledge is learned: “A’ohe pau ka ‘ike i ka hālau ho’okāhi – Not all knowledge is learned in one school.” Dr. Kathie Erwin, another mover-and-shaker in the educational and public service domain, also shares Dr. Si’ilata’s sentiments about schools not being the be-all-end-all of education. For Dr. Erwin, our power lies in our knowledge systems (personal communication, Tuesday, 5 October 2021). The key to Māori succeeding as Māori and Pasifika succeeding as Pasifika is in how and where they harness their knowledge codes and systems. Pasifika dual language books harness the learner’s innate powers by connecting with their lived experiences.

Making Connections Between Our Funds of Knowledge and Stories/Texts

Look at this text and image…

- What comes to mind when you look at the image?

- What comes to mind when you read the text?

- How have your funds of knowledge and schema shaped your responses to the questions above?

Try this…

- Use your background knowledge to complete this cloze exercise.

- Now turn the page to check your answers against the original text.

- Did your schema match that of the text?

- There is no right or wrong answer.

Reflections

What next? How will this impact my practice going forward?

I need to privilege the rich array of linguistic and cultural schemata that my ākonga bring into the classroom. The texts I use need to reflect back the lived experiences of my ākonga.

Before this presentation, I was concerned about my ākonga who were arriving to me with a poor command of their stronger language (English). However, I need to recognise that school English is only one register or variety of English. All varieties of language (i.e., Māori-English, Samoan-English, Tongan-English, etc.) must be treated with respect, mana, and tapu. According to Dr. Si’ilata, “If it’s used to communicate, it’s a valid linguistic code” (Si’ilata & Hansell, 2021). I must aim to add school English and Te Reo Māori to their linguistic repertoire, not replace them. I am not, as Dr. Si’ilata says, just a teacher of content, but I am also a teacher of the language of my subject.

Some wonderings:

My wondering is, how could I incorporate these ideas when teaching Te Reo Māori as a second language to my ākonga? For many, if not all, of my ākonga, English is their stronger language. My ākonga Māori herald from low-income urban homes and are mostly 3rd or 4th generations removed from their papakāinga or ancestral homes where their cultural and literacy practices are performed and upheld. Although some tikanga and literacy practices are retained in some homes, my ākonga do not have exposure to their heritage language and practices outside of my classroom.

References

- Cummins, J. (1981). The Role of Primary Language Development in Promoting Educational Success for Language Minority Students. In California State Department of Education (Ed.), Schooling and Language Minority Students: A Theoretical Rationale (pp. 3-49). Los Angeles, CA: California State University.

- Education Gazette Editors. (2020). Bilingual Approaches Open Linguistic Spaces. Education Gazette, 99(16). Retrieved from: https://gazette.education.govt.nz/articles/bilingual-approaches-open-linguistic-spaces/

- García, O., & Kleifgen, J. A. (2020). Translanguaging and Literacies. Reading Research Quarterly, 55( 4), 553– 571. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.286

- McKenzie, R., & Singleton, H. (2009, October). Moving from Pasifika immersion to Palangi Primary school. Knowing the learner is precious. Paper presented at the Exploring Effective Transitions Conference, Novotel, Hamilton.

- Si’ilata, R. & Hansell, K. (2021, April 16). Ko te Kāhui Ako o Manaiakalani Teacher Only Day [Google Slides]. Manaiakalani Education Trust: https://sites.google.com/manaiakalani.org/manaiakalaniteacheronlyday2021/keynote

- Tamati, S. T. (2016). Transacquisition Pedagogy for Bilingual Education: A Study in Kura Kaupapa Māori Schools. (n.p.): University of Auckland.