Observation of Te Rangihakahaka Centre for Science & Technology | Friday 22 July 2022

Away School Visit #4

Ngāti Whakaue iho, Ngāti Whakaue ake

Kepa Ehau (Ngāti Rangitihi)

The above whakatauāki was identified by whānau, hapū, and iwi as the school’s overarching vision. Through wānanga this vision manifested into Te Rangihakahaka.

Te Rangihakahaka is a kura hourua or partnership school that works outside of our country’s school state system, a system according to principal Renee Gilles, that continues to fail their tamariki. Recognising the need for something better for their tamariki, whānau and hapū members held and hosted wānanga over a three year period. These wānanga gave birth and grew into the whānau, hapū, and iwi driven kaupapa, that is Te Rangihakahaka. Te Rangihakahaka marries both local mātauranga Māori and science, theory and practice into an intricately carved kaupapa that promotes Ngāti Whakaue enjoying educational success as Ngāti Whakaue within a modern world. It is truly innovative!

At Te Rangihakahaka there is a strong sense of belonging among the tamariki. Parents feel connected and love that they are able to just walk in and make themselves at home. Due to the strong sense of belonging, engagement levels are high and they are not dealing with behavioural issues.

Their biggest concern is for the tamariki leaving Te Rangihakahaka to go to secondary school. “This [secondary school] system is very rigid,” states Renee (22 July 2022).

Learning Cycles

The tamariki at Te Rangihakahaka work on one kaupapa each term, and these are called ‘learning cycles.’ When co-designing these learning cycles with their whānau and tamariki, Te Rangihakahaka are always thinking of ways to provide opportunities for ākonga agency. Renee states the importance of taking their tamariki through the inquiry process and the kaiako assuming the role of facilitator so as to allow for ākonga to have agency over their own learning.

When they first opened in 2018 they began with Whakapapa and Genetics in term 1 (see image below). It was imperative for Renee to make their tamariki’s foundations strong. For Renee, “identity, language, and culture is [sic] key as those are the foundations for outcomes.” Without reinforcing and strengthening these foundations, there is no learning.

“Identity, language, and culture is [sic] key as those are the foundations for outcomes.”

Renee Gillies, 22 July 2022

In term 2 they looked at Ara Ahi and Geothermal Activity. It is not enough for Renee to just read and write about learning content, but they must be out there doing it. For instance, the tamariki did not just study the theory about their puna ngāwhā, but they went into their own local areas to observe, study, swim, bathe and cook in them. The tamariki also learned the names of each individual puna ngāwhā in their area through waiata, and ancient mōteatea. Ākonga, as part of this learning cycle, also compared how council looks after the geothermal activity field in Huirau compared to how their people look after their geothermal pools in Whakarewarewa.

In term 3, they looked at Pātaka Kai (food and medicines), where they planted, grew, ate, and sold their produce by hosting a Farmers Market.

They create kaupapa and learning cycles based on the maramataka of their local environment and what is readily available around them, i.e., geothermal pools, Whakarewarewa, awa, marae, local experts, māra kai, etc. Although they did not know it at the time, they were essentially creating a localised and place-based learning curriculum, which is currently being pushed and pitched at all secondary schools around the motu by the Ministry of Education.

Serving and Giving Back to the Community

Te Rangihakahaka dedicates a morning a week to serve their community. “In this day age, they [the ākonga] think it’s all me, me, me, me, but we teach them no, you got to give back to your community” (Renee Gillies, 22 July 2022) This could include picking up rubbish, helping at the SPCA, singing songs and playing chess with the elderly. In the afternoon they look at what their passions are.

Rautaki Reo

Dr. Anaha Hiine put together a reo strategy on how they would implement the reo in their kura. In order for this strategy to work, however, “they need to love our language, first and foremost, and love who they are” (Gillies, 22 July 2022).

“They need to love our language, first and foremost, and love who they are.”

Renee Gillies, 22 July 2022

Short Term Goals: te reo Māori and tikanga are not modernised or religious. They look to Te Ao Tawhito for their karakia, waiata, and whakapapa.

The whole kura come together in the morning to karakia, to recite whakapapa, pepeha, and waiata, which are lead by teh ākonga. At 3:45pm, the whole kura come together again to karakia. Tamariki learn their whakapapa from Tūhourangi all the way down to Ngāti Whakaue. These are just some of the ways that they have been implementing the reo into their kura.

Ngāti Whakaue succeeding as Ngāti Whakaue.

Despite the majority of the student body being descendants of Ngāti Whakaue, there is a small percentage of them who do not whakapapa to Ngāti Whakaue. They push ‘all’ their ākonga, of diverse whakapapa and needs, to seek knowledge in order that they may be uplifted, and that they thrive. If they thrive, the whānau thrive, and if they whānau thrive, the hapū thrive, and if the hapū thrive, the iwi thrive.

Te Pou Matangirua me ngā Kaiako

From left to right: Taylora Haumaha (Kaiako-Teacher), Rneee Gillies (Pou Matangirua-Principal), Rāhera Kiel (Kaiako-Teacher). These were the wonderful wāhine who hosted Te Ahitū. Hore he painga i ēnei tokotoru mō te manaaki manuhiri, me te whakahaere i tētahi kura hourua pēnei i Te Rangihakahaka.

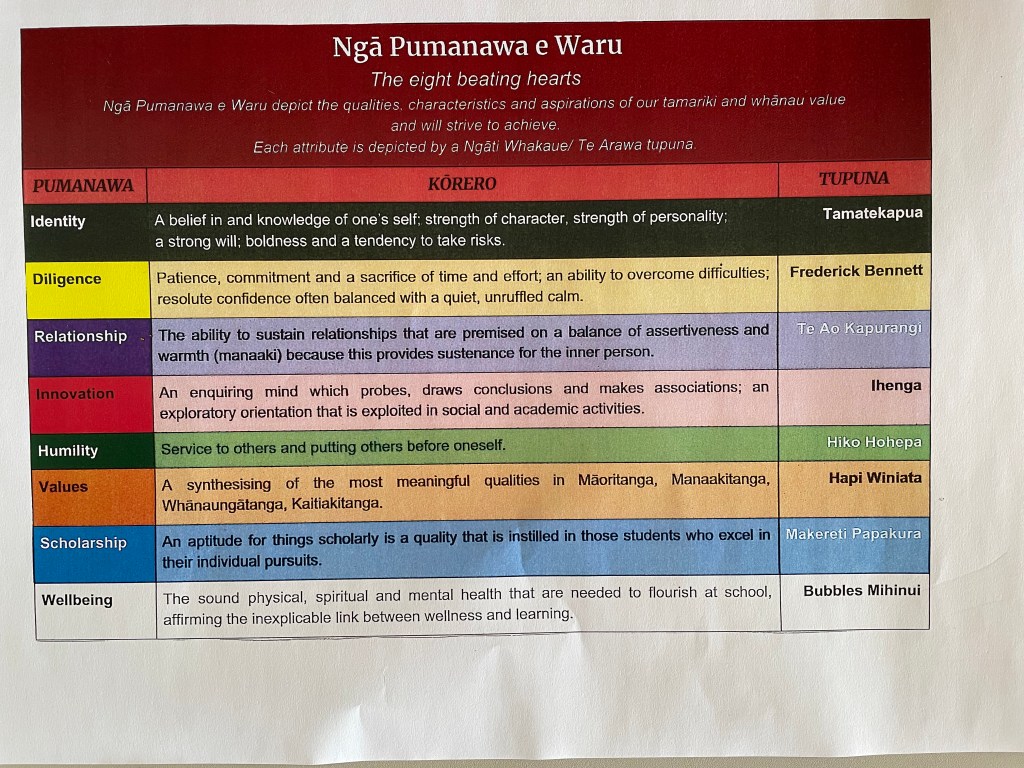

Ngā Pūmanawa e Waru

Ngā Pūmanawa e Waru are Ngāti Whakaue/Te Arawa tūpuna qualities and attributes that their tamariki strive for. All the tamariki can whakapapa to these eight tūpuna. These are the criteria by which kaiako measure the success of their tamariki at Te Rangihakahaka in their reports.

Te Whareaonui

Te Whareaonui draws inspiration from the traditional tāniko pattern Aonui or Aronui, which symbolises the pursuit of the knowledge within their natural environment. This is Te Rangihakahaka’s guiding philosophy for designing their curriculum. “This philosophy motivates us to be active Kaitiaki of our environment. It teaches us to plan methodically, to build a strong foundation, to move forward, reflect, refine and then move forward again. In everything that is created at Te Rangihakahaka this guiding philosophy is evident” (school website).

Te Maramataka o Te Arawa

Planning around the Maramataka

Activities are planned around the maramataka of Te Arawa. It is important that when they are planning their lessons, kaiako need to factor in the maramataka. Kaiako Rāhera Kiel is an avid user of reflective journals and templates. She uses the marakataka for reflections, observations, and for long term planning.

Te Rangihakahaka looks at the maramataka to see:

- when it is a good time to go out

- when it is a good time to go to their awa

- when it is a good time to go to their ngahere

- when it is a good time to plant their māra kai

- when it is a good time to have a staff hui

Rāhera Kiel is a strong advocate for maramataka journaling and reflecting. Rāhera uses the maramataka in her teaching and learning. As a kura that seeks the knowledge within their natural environment, “it was so natural to integrate maramataka into our kura,” says Rāhera (July 22, 2022). Rāhera encourages us kaiako to go to wānanga maramataka in our rohe as it is very place-specific.

Go to the https://ngapatakakorerootearawa.org for maramataka rauemi specific to Te Arawa.

Ētahi Pātai: Q & A

What advice could you give kaiako who are trying to work outside of the box [system] in their mainstream schools?

- “Just do it!”

- “Take the risk”

- Do the hands-on first stuff first and then do the theory stuff later. Integrate the hands-on stuff with the learning content.

- Make your classroom a home away from home.

- We need to role-model what type of learner we are wanting to teach and grow.

- Build strong relationships with your community.

- Don’t let the planning consume you. Look at the maramataka for guidance.

Renee Gillies & Rāhera Kiel

For us kaiako who are not mana whenua, who are teaching tamariki who are a melting pot of different iwi from around the motu, and who also are required to work within a syllabus [i.e. Te Aho Arataki Marau] , what advice do you have for us?

- Treat the syllabus as a guideline.

- It is important to have a stronghold on who the mana whenua are in your area. Help the tamariki to know where they are from, but also where they are currently staying.

Renee Gillies

Reflective Thoughts | Whakaaro Huritao

After our visit to Te Rangihakahaka, I asked myself: Why is Te Rangihakahaka so different to Tāmaki College? How do I incorporate mana whenua into the learning curriculum? What challenges could I possibly face? What things can I take from this observation and implement into rebuilding the Māori department at Tāmaki College? What are some solutions? Below are some of the reflections I had while attempting to answer these questions. Challenges and solutions are sprinkled throughout these reflections.

Why is Te Rangihakahaka so different to Tāmaki College?

Te Rangihakahaka, for me, is a beautiful dream. Te Rangihakahaka is a kura that is built on mana whenua land, by mana whenua, for mana whenua. The reality for many of us kaiako Māori living and teaching in Tāmaki Herenga Waka, is that we teach in state-owned schools often in areas where we are not mana whenua, and where ākonga are a melting pot of different iwi and ethnicities. Te Rangihakahaka is a Kura Hourua or Partnership School. As a Kura Hourua, Te Rangihakahaka have more flexibility about how they operate and use their funding, therefore they have the freedom to develop innovative solutions to meet the educational needs of their tamariki, this includes how they design their curriculum. As state school kaiako we are required to work within a progressive syllabus (i.e., Te Aho Arataki Marau) and are pressured to meet the assessment demands of NCEA. The only innovative interventions we can hope to implement are within the confines of our classrooms. Whole school implementation requires teacher, whānau and leadership buy-in.

Ākonga in Te Rangihakahaka are 90% Ngāti Whakaue and are being raised and educated near their pā in Ōhinemutu. The majority of ākonga Māori in Tāmaki College are fourth and fifth generations removed from their own papa kāinga, language, and culture. They have not had the luxury or opportunity to reconnect with their ancestral lands, people, language, and culture. Therefore, the love for their language and culture has not been cultivated. That is not to say that they are not yearning for these things because they are starving.

Staff buy-in is where the greatest impact can be made for Māori cultural pride and visibility, and more importantly, for our Māori students. At Te Rangihakahaka everyone, including staff, whānau, ākonga, hapū, iwi, and marae are in synchronicity. They share the same vision and the same why. However, only a small percentage of staff are on board at Tāmaki College, and this is evident in their continuous lack of involvement and appearance in things Māori, including pōwhiri, haka, waiata, karakia, Matariki Celebrations, and Māori Language Week. If staff really wanted positive change for ākonga Māori, I would not be the only one trying to raise Māori cultural visibility and pride, which has been the case for the last three years that I have been teaching at Tāmaki College. There is a sense of indifference and aloofness when it comes to Māori culture. It is understandable. After-all, they are not Māori, they don’t live as Māori. There may be a lack of integration and connection with Māori in general. This is also reflected and exacerbated in the school context where integration between departments is non-existent. We really need to learn from schools like Te Rangihakahaka and kura kaupapa Māori where ākonga are soaring and thriving academically, culturally, socially, and spiritually.

From my own professional judgement, without first addressing these foundational needs of our ākonga in any school, that is, their identity, language , and culture – the identity/ foundation works – there will be no outcomes in Te Reo Māori. As simple as it may seem to help my ākonga reclaim their lost heritage, it has proven to be an arduous task. I am having to break through intergenerational barriers of trauma, loss, mistrust, hurt, prejudice, and stigma that go back four to five generations, perhaps even more. Unfortunately, this is generally a task that only the one or two kaiako Māori in mainstream schools are qualified to do or most often delegated. I am not saying that non-Māori kaiako are not able to help our ākonga Māori. I am just saying that the stakes are higher for kaikao Māori.

How do I incorporate mana whenua into the learning curriculum?

Incorporating mana whenua into the learning curriculum, I believe, can only go as far as the pūrākau/pakiwaitara and hītoria. Even then, we must seek permission to use or teach these. I don’t feel it is right to use whakatauākī, whakataukī, pepeha, and tūpuna names and attributes belonging to mana whenua in the design of my curriculum and philosophy for my department. These belong to Ngāti Pāoa, and Ngāti Pāoa only. In fact, it is impossible to teach a “melting pot” school of students about one specific iwi. Identity, culture, and the language taught in mainstream schools such as Tāmaki College, is usually a blanket “Māori” one. We kaiako Māori search for commonalities: what do they all share? They are Māori. Who do they all descend from? The Atua Māori, particularly Tāne Mahuta and Hineahuone.

What things can I take from this observation and implement into rebuilding the Māori department at Tāmaki College?

- The Pūmanawa e Waru criteria have inspired me to do the same thing, but instead of tūpuna I will use Atua Māori. I need to think of one quality or attribute for each Atua Māori, and design a leadership programme or Māori student mentoring group using this. I will need to research the seven main Atua tāne, and the seven main Atua wāhine. According to a source from Te Whare Tū Taua, for every male Atua there is a female equivalent.

- Create learning cycles or units based on the needs and hiahia of the community, whānau, and ākonga. Include plenty of opportunities for hands-on mahi. Look at what is around us and the maramataka for this rohe.

- Wānanga with whānau what our why is and co-design a philosophy around this.

- Ask to form a Māori mentoring group, that will be taught how to lead kaupapa māori in school and in the community.

- Contact Ngāti Whātua o Ōrākei or Ngāti Pāoa for wānanga and rauemi maramataka for this rohe for 2023 so that I can plan my trips, hui, units, lessons, and assessments for next year.

- Host a staff noho marae to wānanga about problems and solutions regarding ākonga Māori.